Although history never repeats itself, it is a useful teacher and we ignore its instruction at our peril. To understand the nature of Western democracy’s current crisis, we must look for historical parallels that can help to illuminate the instability that we are experiencing.

The Weimar Republic (1918–33) is often taken as the paradigm of a failed democratic experiment. Forged in the immediate aftermath of Imperial Germany’s defeat in the First World War, it was designed to be a constitutional liberal democracy that opened the way to a new progressive future for the country. Instead, it suffered from chronic political instability, which was deliberately aggravated by strongly anti-Republican forces on the far-right and far-left, both of which launched uprisings and coup attempts in the initial five years of the Republic. Weimar was also rocked by two major economic crises that undermined its viability, and beset by difficult relations with the Western allies that had defeated Germany in the war. Following widespread political violence and constant civil turmoil throughout its fifteen year tenure, it finally collapsed with the Nazi rise to power in 1933.

It is not uncommon to use the Weimar Republic as a standard of evaluation when assessing the relative health of democracies under pressure. The British historian Richard Evans did so in his annual Provost Lecture at Gresham College on 18 June 2019 titled “The Weimar Republic: Germany’s First Democracy.” While acknowledging the recent rise of authoritarian regimes and anti-democratic movements throughout the world, Evans focussed on significant differences between Weimar and the current situation in the West.

Specifically, Evans noted the comparatively low level of political violence in Europe and North America today compared to the first German republic. He pointed out that the legislatures in Western countries remain effective centres of government power. Germany’s then-president, Paul von Hindenburg, invoked article 48 of the German constitution to justify direct presidential rule by decree in March 1930, rendering the Reichstag largely irrelevant. This enabled his appointment of Hitler to the chancellorship after the election of 1933. Evans remarked that the far-right and far-left oppositions in Weimar both sought to destroy the Republic, but that contemporary right and left populist movements are, for the most part, operating within their respective constitutional frameworks. He also observed that there was growing danger of global conflict in the period that followed the fall of the Republic, which he regarded as largely absent at the time of his lecture.

However, in the six and a half years since Evans presented his talk, we have experienced the COVID pandemic, the 6 January 2021 assault on the US Capitol, the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the Gaza War, a sharp increase in openly expressed antisemitism, Trump’s election to a second term, the unravelling of international trade agreements due to Trump’s erratic tariff campaign, increasingly extreme measures against immigration, and a range of related developments. It is therefore worth revisiting the comparison between the current state of the West and the Weimar Republic in light of these events.

The birth of the Weimar Republic was accompanied by violent resistance from its opponents. The army and most of the right wing of the political spectrum were aggrieved by Germany’s defeat in the war, and by what they regarded as the humiliating terms of the Versailles Treaty. The far-left, on the other hand, regarded the Republic as an instrument of the bourgeoisie used to preserve the capitalist order and exploit the German working class. In January 1919, the Spartacist uprising in Berlin, led by Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg, attempted to replace the nascent Republic with a Soviet-style revolutionary government. It was suppressed by the ruling Social Democrats, who used right-wing military units to put down the revolt. Both Liebknecht and Luxemburg were murdered in the course of these events. The Nazi SA paramilitary force, led by Hitler, together with völkisch far-right allies, attempted a coup in Munich in November 1923. It was aborted by the army and Bavarian state police. Hitler and other coup leaders were jailed for several months, and the activities of their political organisations were tightly curtailed.

After these unsuccessful revolts, both the Nazis and the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) adopted strategies to overthrow the Republic by working within the constraints of its constitutional system. They competed in federal and state elections, but they also sustained a constant stream of intense extra-parliamentary agitation in the streets, in the press, in labour organisations, in youth movements, and throughout Germany’s professional and educational institutions.

Weimar was roiled by a severe economic crisis in its first five years. The Versailles treaty imposed heavy reparations on the new government, and it experienced hyperinflation. French and Belgian troops occupied the Ruhr region of the Rhineland in January 1923, when Germany defaulted on its payments. This further inflamed antagonism towards the Republic within the army and among nationalist elements of the electorate. The situation improved significantly with the signing of the Dawes Plan in 1924. This arrangement restructured the country’s foreign debt and made substantial American loans available. A currency reform was implemented that ended hyperinflation, and allied troops withdrew from the Ruhr in August 1925. Economic growth picked up, and a measure of prosperity was achieved.

The economic improvement in Germany after 1924 introduced a period of relative stability that lasted until the depression hit in 1929. During these five years, the anti-Republican forces were marginalised within the Reichstag as voters shifted back to the Social Democrats (SPD) and the various centrist parties. In the federal election of 1928, the SPD emerged as the largest party, with 29.8 percent of the popular vote, and led a large centre-left coalition government. The Nazis received only 2.6 percent of the vote, while the KPD went from 8.9 percent to 10.6 percent. With the start of the depression, however, the American loans that had mitigated the burden of Germany’s foreign debt were withdrawn. Mass unemployment surged, and the electorate gravitated to the extreme anti-Republican parties. The Nazis quickly moved from being a splinter group in parliament to a mass movement of the middle and working classes. Interestingly, even in the 1933 elections they failed to obtain a majority of seats, scoring 43.9 percent, with the SPD in second place (18.3 percent) and the KPD in third (12.3 percent). Hindenburg’s decision to hand the chancellorship to Hitler ended Germany’s experiment with democracy and ushered in the catastrophe of the Third Reich.

The results of the Weimar elections seem to indicate that extremism only became a significant political force in periods of severe economic upheaval, but this is not true. While the electoral fortunes of the anti-Republican parties do indeed track the economy, these movements played a major role in shaping the extra-parliamentary environment of the Republic throughout its history. In The German Dictatorship: The Origins, Structure, and Consequences of National Socialism, the German historian Karl Dietrich Bracher provides what remains one of the most authoritative and meticulous accounts of the Weimar Republic and the Nazi regime that followed it.

Bracher observes that all the major political parties maintained paramilitary forces that engaged in propaganda and street violence. The Nazis emerged out of a larger array of völkisch nationalist movements that regarded capitalism, liberalism, communism, and Jews as mortal threats to the revival of the German nation. They pursued a deeply reactionary, tribal notion of nationhood, with the Republic portrayed as an instrument of foreign control. It is from this toxic mix that national socialism emerged. It combined anti-rationalist romanticism, racist theories of ethnicity, and hostility to modernism, construed as destructive of healthy organic community. Jews—identified as agents of capitalism, liberalism, and Marxism—were cast as the instantiation of this corrosive modernism.

The KPD, for its part, targeted its primary adversary, which was not the Nazi Party and the völkisch right from which it came, but the Social Democrats, whom the communists described as “social fascists.” Following the Comintern policy set by Stalin, the KPD also sought the destruction of the bourgeois Republic, which they believed was the main instrument for capitalist exploitation of German workers. The anti-capitalist hostility to liberalism driving both movements defined a peculiar consensus between opposing extremes. This consensus played a central role in the unravelling of the Weimar democracy.

Nazism is commonly thought of as a disease of the uneducated and the lower middle classes, but this was not entirely the case. Bracher points out that the legal and medical professions and the judicial system were strongholds of völkisch sentiment. The Nazis colonised the German universities. Their supporters took over the student unions, and professors were largely supportive of these groups. He also notes that Nazi students and academics—who engaged in constant (and often violent) agitation, and who politicised university curricula—justified their behaviour on the grounds of academic freedom. Young people flocked to the Hitlerjugend, and other far-right youth movements. Nazism was very much a movement of the youth, particularly of students. University administrators generally refused to oppose this student-led seizure of their institutions, either out of fear of retribution, or because of sympathy for its agenda.

Many commentators discussing the current political scene point to the role of digital platforms and social media in facilitating the rapid spread of extremism. The propaganda campaigns that radicalised large segments of public opinion in the Weimar Republic clearly show that digital technology is not required to produce a complete breakdown in democratic norms. The anti-Republican forces in Weimar managed to achieve this effect quite efficiently through low-tech methods of mass communication. They used blanket leafleting, newspapers, placards, marches, mass meetings, paramilitary parades, films, and radio (then still a fairly new medium) to create a relentless, disorienting barrage of political messaging. They had no problem in generating widely accepted disinformation, despite not having smartphones, Instagram, or X.

Antisemitism was one of the primary factors animating Weimar politics. The völkisch far-right referred to Weimar as the “Jew Republic” and held “international Jewry” responsible for Imperial Germany’s defeat (the stab-in-the-back accusation). “Jewish financial capitalism” was said to be the source of Germany’s economic problems and Jewish cultural influence was a parasite destroying Germany’s greatness.

The KPD officially condemned antisemitism and the racial theories of the völkisch Right. However, it frequently borrowed attacks on “Jewish capitalism” from this quarter to sustain credibility with some of its voters. The identification of capitalist exploitation with Jews was common in parts of the European Left throughout the 19th century. It is on prominent display in Marx’s Die Judenfrage (“The Jewish Question”) pamphlet published in 1843. The KPD analysed antisemitism as a side-effect of capitalism used to divert the attention of workers from the exploitation that they suffered at the hands of their employers. It would disappear, along with Jews as a distinct cultural group, when the revolution created a classless workers’ society. Anti-Jewish hatred and the Jewish communities at which it was directed were both dismissed as epiphenomena rather than a proper cause worthy of mobilised communist opposition.

In accordance with Comintern policy, the KPD rejected Zionism as a reactionary movement designed to promote Jewish particularism associated with Nazism, fascism, and imperialism. During the 1920s, violent Arab–Jewish conflict erupted in Mandatory Palestine when Arab irregulars attacked the Yishuv (the Jewish community there), culminating in the Arab riots of 1929. These began in Jerusalem over the Western Wall and the al-Aqsa Mosque, then spread to other cities, resulting in heavy casualties and the destruction of the ancient Jewish community of Hebron. In response, the Yishuv organised a self-defence force that became the basis for the Haganah. Opposition to Jewish immigration and settlement grew among Palestinian Arabs just as refugees began fleeing anti-Jewish violence in Europe. The KPD adopted the Comintern view that the Arab attacks on the Yishuv were an expression of progressive resistance to Zionist colonialism sponsored by British imperialism.

Hostility to British and French interests in the Middle East produced another peculiar convergence between the two extremes of Weimar anti-Republican politics. In 1928, Hassan al-Banna founded the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, which developed into the main agent of Sunni Islamism, and Amin al-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, became the leading figure in the Palestinian national movement. The Nazis and the Italian fascists sought influence among Arab nationalists and Islamists throughout the Middle East in order to undermine the British and French presence there, and some Arab nationalists and Islamists returned that support for the same reason.

Hostility to immigrants was a völkisch obsession, and in the Weimar Republic, the far-right raged against East European Jews who had fled the pogroms of pre-war and inter-war years. These migrants were presented as a drain on the country’s resources, subversive agents of socialism, and culturally alien undesirables. In covering several high-profile scandals involving East European Jewish businessmen, the KPD press employed the racist anti-Jewish terminology popular in völkisch circles to retain support among workers increasingly drawn to the far-right.

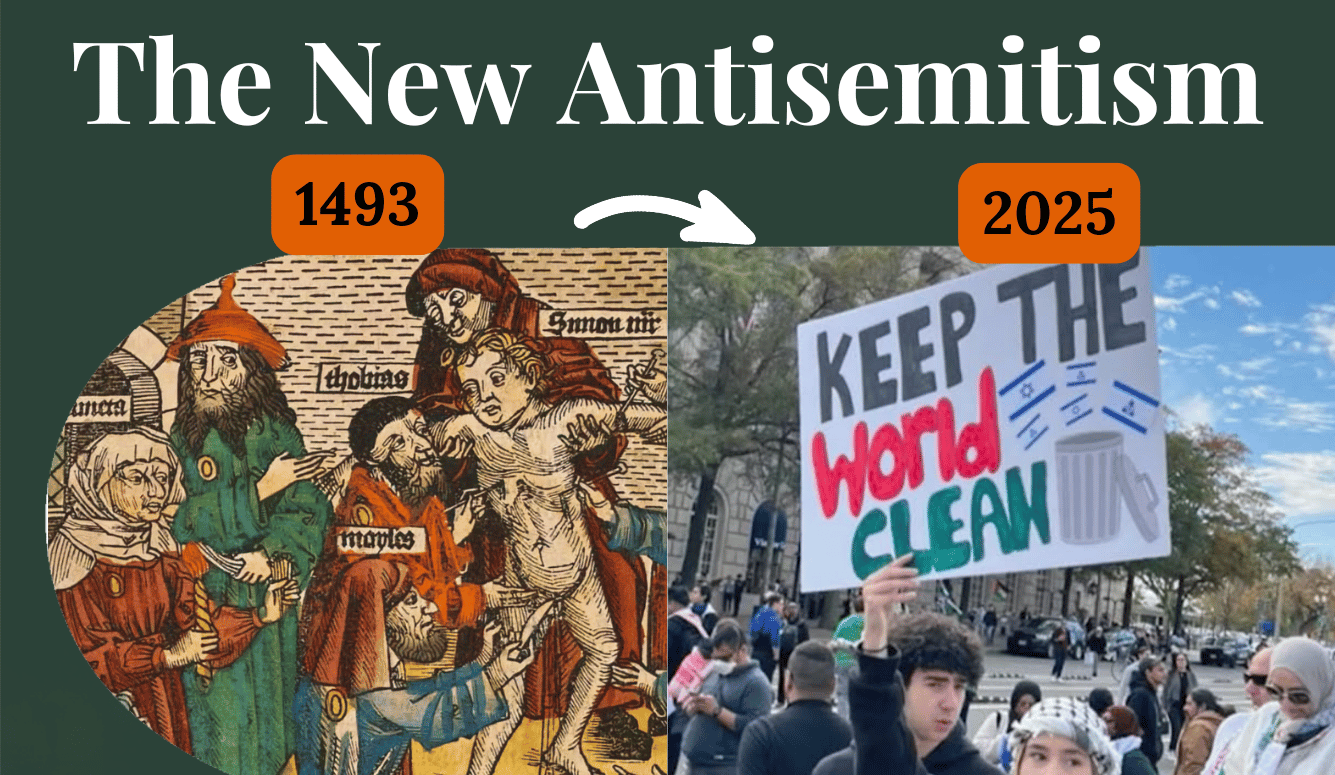

The racialised antisemitism of 19th-century European ethnonationalists provided the basis for völkisch antisemitism in the Weimar Republic. It was a messianic worldview in which the Jews were assigned an eschatological role as demonic agents who manipulated world events to generate corruption and evil. Eliminating them was the means to global redemption and restoration, and the Nazis operationalised this conspiratorial delusion into a concrete political program. First, they dehumanised Jews in the public consensus through a relentless campaign of defamation, then they excluded them from the civic realm. Finally, they physically annihilated them. The first two phases of this operation were well underway in the latter years of the Republic.

The parallels between conditions in the Weimar Republic and in much of the West (and beyond) today are stronger now than they were when Evans delivered his Provost’s Lecture in 2019. In his second term, Trump has shredded constitutional norms as he seeks to govern by presidential decree. He has flooded American cities with National Guard and ICE troops, terrorising immigrant communities. There has been a significant increase in political violence, particularly in America, from both the Right and the Left, and assassinations of political figures from both sides. Attempts to use the courts to restrain Trump’s assaults on democratic institutions have enjoyed very limited success. The Supreme Court has become largely a facilitating spectator rather than a judicial arbiter of government power in its response to the numerous appeals brought against the administration. Far-right ethnonationalist parties are surging across Europe and in Latin America, India, and Turkey. Many have already ascended to government or become part of governing coalitions, and they look to Trump as a model.

Trump has subordinated the Republican Party entirely to his own personal and political agenda, eliminating what remained of its moderate conservative elements. Beyond the chaos that pervades his second term, a new generation of far-right extremists is taking shape around the party’s neo-isolationist wing. Some of its leading members are promoting explicitly neo-Nazi ideas, which are gaining currency among young supporters through social media and podcasts. Many of these extremists are critical of Trump and regard themselves as the next generation of the MAGA movement. They have adopted the same conspiracy-ridden antisemitism that pervaded the Weimar Republic and discoloured so much of its political life.

At the same time, an alliance of Islamists and the postmodernist Left now defines the leading edge of leftwing political activism. It is rampaging through the universities and marching in the streets of Western cities. It is fixated on a messianic anti-Zionism as the core of its “anti-colonialist” doctrine. This ideology is not focussed on criticism of Israel’s policies and actions. Such criticism is legitimate, and, in many cases, well warranted, particularly in the case of the Netanyahu government. Nor is its leadership motivated by the massive suffering of innocent Palestinian civilians caught in the terrible war in Gaza, which is a similarly reasonable concern. This is a movement that seeks the obliteration of Israel as a country by “any means necessary” and the elimination of its Jewish residents, who constitute half of the world’s Jewish population. That goal would require either expulsion or slaughter of the kind that Hamas committed in its mass terrorist assault on 7 October 2023, an attack that much of this movement celebrates as heroic anti-colonial resistance. The monomaniacal hatred that this movement directs at Israel as a country—and at all Jews who insist on its right to exist—is unique. It is unknown in any other political context that features brutal conflicts and oppressive regimes.

The current anti-Zionist campaign of the Islamist-postmodernist left coalition bears more than a passing resemblance to the anti-Jewish racism of the Weimar far-right. It invokes the same cosmic conspiracy theories of Jewish/Zionist control of financial capitalism, the media, and levers of political power. It shares with völkisch antisemitism the view that eliminating Jewish collective existence, in at least one domain, is the route to redemption. This movement targets diaspora Jewish communities for violent exclusion to the extent that they do not endorse its anti-Zionist cult.

The progressive coalition relies heavily on ethnic and gender-based identity politics to mobilise a sense of grievance in the constituencies that it purports to represent. While many of its leading figures describe themselves as “democratic socialists” the conduct of the more radical members of this alliance is suggestive of the national socialism of the Weimar far-right. They are becoming a significant factor within the Democratic Party, with growing support from young people. The extreme pro-Hamas edge of this coalition has attracted a growing coterie of apologists and fellow travellers in what now passes for the mainstream Left. They and their counterparts in Europe are defining fashionable opinion in formerly liberal political and cultural circles.

Like previous forms of antisemitism, the current variety arrogates the right to characterise the Jews as a people. It tells them who they are, and it instructs them on what they ought to be. When Karl Lueger, the early-20th century Christian Social mayor of Vienna, was criticised for befriending prominent members of the Jewish community while promoting virulently anti-Jewish political ideas, he is reported to have replied “I decide who is a Jew.” On 19 November 2025, the Palestinian Assembly for Liberation conducted a noisy anti-Israel demonstration, complete with violent slogans of intimidation and racist insults, outside an Upper East Side Manhattan synagogue, where an information session on immigration to Israel was taking place. Zohran Mamdani, the mayor-elect of New York, described the event hosted by the synagogue as a misuse of sacred space. Like his associates in Students for Justice in Palestine, he too is instructing Jews on who they are and what they must do.

As it did in Weimar, economic instability is driving the current rise of extremism. The export of industrial manufacturing from the West to China and countries in the developing world over the past thirty years has caused major social dislocation. It has generated acute inequality in the distribution of wealth within Western (as well as non-Western) nations. This has displaced large portions of the working, rural, and middle classes, depriving them of the long-term security that they had enjoyed in the postwar era. Centrist and social-democratic governments have been unable to deal effectively with this disruption. Much of the upheaval has been conditioned by globalising financial and economic trends that they have not succeeded in harnessing for general social benefit. The result has been an acceleration in radical movements that exploit popular disaffection by blaming liberal urban elites in the West for the misfortunes that beset the constituencies that these movements claim to represent.

The emergence of powerful deep-learning models of AI applied to a variety of tasks is now creating a new wave of technological change and introducing automation across a wide range of tasks. This could produce serious pressure on the job market, particularly in skilled entry-level positions in a variety of fields. If this change is managed as badly and as haphazardly as the deindustrialisation process facilitated by globalisation, then it may seriously intensify the trend towards extremist politics that is currently gripping the West.

The threat to global security, which was not apparent when Evans gave his talk in 2019, has now come into clear view. An axis consisting of Russia, China, and Iran is dismantling the geopolitical order at a rapid rate. Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 exposed the Obama and the Biden administrations’ folly of indulging Russian aggression in Crimea, eastern Ukraine, and Georgia. Far-right parties in the West have been, for the most part, supportive of Putin as a nationalist hero in their own mode. The far-left, even when critical of Putin, portrays him as provoked by NATO’s expansion. He is, on this account, a victim of Western imperialism, rather than an agent of aggression in his own right. They dismiss the fact that the former Soviet countries joined NATO because they reasonably feared Russian invasion, and they redescribe accession as a Western expansionist plot. Trump has been pursuing a policy of transactional appeasement towards Putin, while the European countries have been diffident in their support of Ukraine.

Iran’s efforts at regional hegemony in the Middle East have been thwarted (at least for now) by Israeli military action against its proxy armies, and the joint Israeli/American strike on its nuclear program. This has earned Israel the quiet gratitude of moderate Arab countries, and the reflex outrage of most of the Western Left and the isolationist component of the far-right. China continues to cautiously expand its realm of economic and military influence in the Pacific, threatening Taiwan, and other areas. The alacrity with which Trump has torn apart the Western security alliance has made a firm, measured, and coherent response to the threats posed by the axis countries all but impossible. He has contracted out the management of crucial foreign-policy issues to real-estate magnates and family members, and personal business interests are now guiding many of these negotiations.

The way in which diaspora Jews in the West have responded to the wave of antisemitism they are encountering recalls the manner in which Weimar’s Jews dealt with the hatred that engulfed them. Minorities of the German Jewish population joined the anti-Republican extremists. The Association of German National Jews (Verband Nationaldeutscher Juden) was a small group of ultranationalist assimilationists who supported the völkisch far-right. They claimed that, as loyal Germans, they were obliged to subordinate Jewish concerns to the interests of the German nation. They endorsed the Nazi referendum of 1934 that called for Hitler to combine the roles of chancellor and president as absolute ruler of the Third Reich. A larger minority joined the DKP in the belief that a revolutionary workers’ state would provide justice and equality to all, including Jews. Both groups were destroyed in the Nazi genocide.

The Central Association of German Citizens of Jewish Faith (Centralverein Deutscher Staatsbürger Jüdischen Glaubens) represented the mainstream of Weimar German Jewry. It was similar to today’s American Jewish Congress, the American Jewish Committee, the Board of Deputies of British Jews, Le Consistoire Central Israélite de France, and other broad-based communal organisations throughout the West. During the years of the Republic, it lobbied for Jewish concerns, as it sought to oppose anti-Jewish activity, and its members promoted liberal and moderate pro-Republican attitudes. It relied on informational campaigns, legal action, and appeals to government agencies. By the latter stages of the Republic, these methods were of little use in dealing with a political environment set ablaze by competing currents of extremism.

A very similar pattern obtains today in the way that diaspora Jews in the West are attempting to come to terms with the disintegration of the liberal order in which they had flourished during the postwar period. Minorities of Jews have been co-opted to the far-right, and to the anti-Zionist far-left. The mainstream community continues to rely on its representative organisations to sustain informational campaigns and to launch legal actions against the rising tide of harassment, violence, and exclusion to which they are being subjected. There is no reason to think that these methods, suited to times of stability and social cohesion, will be any more effective now than they were in the Weimar era.

There are, however, also important points of divergence between the current crisis of democracy and the Weimar Republic. One of them is, unfortunately, not a source of solace. While the chaos of the Weimar Republic played out in Germany, the current breakdown of liberal democracy extends through most of the West. The intense antisemitism that drove politics in Weimar existed in other countries, particularly in Austria and Hungary, but it was not universal. Even fascist Italy did not adopt it until Mussolini introduced the racial laws of 1938. Today’s right-wing, left-wing, and Islamist versions of anti-Jewish hatred are prominent throughout Europe, North America, and Australia. Economic instability and the political extremism that it is creating are now general features of the West and many other parts of the world.

But there are other, more positive differences. One of the reasons that the far-right in Weimar was able to operate effectively was the support that it received from the army and the judicial system, both of which were centres of extreme ethnonationalist sympathy. This is not the case in most contemporary Western countries, where the military forces and judiciaries remain largely apolitical. In addition, while the Western economy is in the midst of rapid, destabilising change, it has not experienced the catastrophic meltdown of the Great Depression, which was the efficient cause of the demise of the Weimar Republic. And while diaspora Jews are exposed, Israel, for all its serious faults, is quite capable of defending itself and it exists as a place of Jewish refuge should Jews’ situation in the diaspora become intolerable.

One of Bracher’s most important and heartening insights is his observation that the destruction of the Weimar Republic was not inevitable. It was the result of specific decisions made by individuals and groups who could have acted differently. The KPD did not have to continue its campaign against the SPD after the 1930 election. It could have joined forces with it and the centrist parties to block the far-right from taking power. Hindenburg and the non-Nazi Right should have recognised that their belief that they could control Hitler for their own purposes was a delusion. Had they done so, they might have acted to stop him. German Jews might have foreseen the dangers that awaited them with the dissolution of the Republic. Had this happened, they could have emigrated en masse to the limited number of accessible places which would have guaranteed their safety.

That these mistakes were made is understandable. The disaster of the Nazi regime was without historical precedent, and it is unreasonable to expect the principal actors of the time to have anticipated a horror of that magnitude, which lay entirely beyond their notion of the possible. The current custodians of liberal democracies have no such excuse available to them. They enjoy the full benefit of historical knowledge. The Weimar Republic stands as a warning of what happens when societies and their citizens indulge extremism. Its record exhibits the folly of collaborating with people intent on destroying democratic institutions, and it illustrates the consequences of failing to protect these institutions when they come under sustained attack.

Unfortunately, many of the moderate leaders of the West have completely failed to internalise these lessons. They are pandering to extremists of the Right, Left, and Islamist insurgencies for reasons of political expedience. They are also appeasing the aggression of axis countries in deference to short-term political and economic interests. Western democracy is now under a late-phase Weimar-like siege. It can still be rescued. But to do this, its adherents must move from passive belief in liberal values to militant resistance against those who are shattering them. This resistance begins by reclaiming historical literacy and moral courage.

In the February/March 2026 issue of Reason, we explore Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani's policy goals and what they mean for New York City. Click here to read the other entries.

When I first took a road trip to New York as a young teen, I was astonished by the industrial landscape as we neared the city on the New Jersey Turnpike. "Why would they put all this dirty stuff so close to the city?" I asked my parents. As a D.C. kid, it had never occurred to me to think about what cities were actually for. In Washington, we mostly make rules and big marble monuments.

That trip was the first time I saw a city driven by commerce and art rather than political power. In the mid-1990s, New York was well past its industrial and shipping heyday, but the signs were still all around. The city was grittier than it would soon be—we were right on the cusp of the major decline in crime that would sweep through nearly all American cities. It was so gritty, in fact, that my parents forbade me from applying to college in New York. They thought the city was too pricey and dangerous, even though they loved it.

Today, the city is much richer and fussier than it was. Parents are still fretting about its dangers and expense. Mayors come and go—remember when Rudy Giuliani was "America's mayor"?—and New York remains fundamentally itself.

Zohran Mamdani won the 2025 mayoral election on a platform that included fare-free buses, city-owned grocery stores, and a rent freeze for rent-stabilized units, plus equity-centered education policy and an oddly status-quo policing plan for a one-time defunder/abolitionist. As this issue of Reason unpacks, there are many reasons to fear such policies will be ineffective at best and deeply counterproductive at worst. And as my parents' diktat shows, when governance and policy get bad enough, that can scare off potential residents and visitors alike.

But a single mayor can't ruin New York City, because New York City is not reducible to policy choices.

New York's incredible power derives in large part from the fact that it's home to a really big pile of money. Big piles of money, especially when they are in private hands, drive innovation and hustle. Big piles of money also throw off charity and patronage of the arts. A mayor can posture, he can regulate, and he can pressure firms in press conferences. He can even scare off investors and entrepreneurs at the margins. But the New York Stock Exchange is headquartered in Lower Manhattan and will be for the foreseeable future, where it remains a giant battery powering the city.

Then there's the city's appealingly unglamorous commercial underbelly. The New York City Economic Development Corporation reports that there are about 183,000 small businesses in the city. Yes, it's annoying that New Yorkers won't shut up about their beloved bodegas—it's just a corner store!—but the insane number and subtle market differentiation of those corner stores are a joy for any night owl, early bird, or regular commuter pigeon.

Black and gray markets thrive in ways made possible by the sheer density and diversity of humanity in the city. The worse governance gets, the more commercial activity will get pushed into these markets, with all that entails. New Yorkers are famous for their workarounds of an utterly bonkers real estate market, for example. It's also part of a vanishing breed of cities where transactions still happen in cash. A Federal Reserve Bank of New York report explains one mechanism by which density raises productivity: Proximity lowers the costs of exchanging information and generating new ideas. The paper estimates that doubling density increases productivity by about 2 percent to 4 percent.

Which brings us to the humans: New York makes visible the consequences of the free movement of people. The sophisticated, slightly impatient people who are born there are a different breed (my husband among them). The Americans who come from all over to try their luck in the big city keep the fire burning (my sister among them). And of course, New York is home to more than 3 million immigrants—about 38 percent of the city population, according to the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs.

***

I visited the city over Thanksgiving this year, blitzing up the turnpike with a family of my own. Now immune to the sights and smells of industrial New Jersey, I marveled at a different apparition: trash cans. Outgoing Mayor Eric Adams' trash containerization push was on display in the streets, and fewer of the city's famous trash bag mountains were visible. The Mayor's Office reports declines in rat sightings in connection with the new rules.

I took the presence of trash cans as a reminder that improvements in governance are possible and worth fighting for. But they were literally and metaphorically dwarfed by the buzz of buying and selling, creating and destroying, visible all around them. New York City has a long history of correcting course after political disasters and absorbing bad leadership, and it will again.

Around the same time as that teenaged trip to New York, I read The Fountainhead (and then everything else Ayn Rand wrote, in rather short order). While it didn't strike me at the time, I've since returned to her words about the city many times—especially after 9/11—for the way she captures the place's powerful self-sufficiency and its terrible vulnerability: "I would give the greatest sunset in the world for one sight of New York's skyline," Rand wrote. "Particularly when one can't see the details. Just the shapes. The shapes and the thought that made them. The sky over New York and the will of man made visible….When I see the city from my window—no, I don't feel how small I am—but I feel that if a war came to threaten this, I would throw myself into space, over the city, and protect these buildings with my body."

What Zohran Mamdani's Rotten Ideas Could Do to the Big Apple

In the February/Mach 2026 issue of Reason, we explore Mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani's policy goals and what they mean for New York City. Read the other entries here:

- Zohran Mamdani's Socialist Housing Plan Could Crash New York's Rickety Rental Market

- The Two Faces of Zohran Mamdani

- Mamdani's Education Agenda for Less Learning

- A Maximalist Vision of Mayoral Power

- Zohran Mamdani's Prices Crises

- Will Mamdani Defund the Police?

- 3 Reasons Mamdani's City-Run Grocery Stores Will Fail

- Mamdani Can't Raise Your Kids

- Meet Zohran Mamdani's Inner Circle

The post Zohran Mamdani Can't Ruin New York City appeared first on Reason.com.