This essay resumes the series of essays that I started to publish two months ago on the ethics of selflessness versus selfishness. Previous essays in the series include “The Moral Issue of our Time,” “The Thrasymachian Challenge,” “Jesus and the Philosophy of Selflessness” and “A Brief (Philosophic) History of Selfishness,”

The audio version of this essay, which I’m making available this week to all subscribers, is below.

The spiritual and existential communism of the early Christians was revived in the seventeenth century with the Anglo-American Puritans, who attempted to revive the ethics of Christian love, sacrifice, mutuality, and communalism. To be right with God, according to the Puritans, meant to live out His commandments in the here and now.

In their attempt to restore true and pure Christianity, the Puritans took the apostolic letters and the Acts of the Apostles as guidebooks for how to walk and follow in the footsteps of Christ and his disciples. The founders of the Plymouth, Massachusetts-Bay, Connecticut, New Haven, and Rhode Island colonies all attempted to create Bible commonwealths that would embody Christ’s ethical teachings.

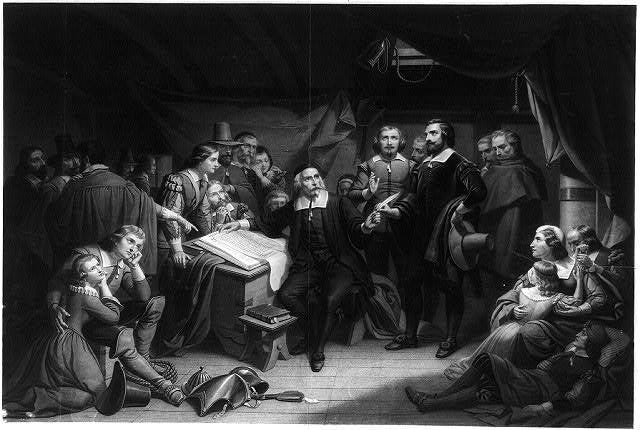

In June 1630, somewhere in mid-passage between England and America, John Winthrop, the great founding statesman of the Puritans’ American experiment, delivered a lay sermon aboard the Arabella to the first wave of emigrants that may very well have been the most important Puritan sermon ever delivered. The title of Winthrop’s ur-sermon was “A Modell of Christian Charity,” which explained to his fellow Puritans the moral ends and standards by which they were to live their lives day-to-day.

The explicit theme of the sermon was the right ordering of man’s soul in relationship first to God and then to his moral, social, and economic relationships with his fellow congregants. More specifically, the sub-theme of the sermon was “love,” which was the transformative moral force that Winthrop sought to inject into the Puritan community. He hoped that Christian love (i.e., the unconditional love of others) would overcome Adams’s disobedience and replace man’s post-Fall state of self-seeking moral degeneracy. Selfishness would be replaced with selflessness, hate with love, envy with respect, and greed with charity. Love was the prime mover at the center of man’s rebirth, and it was the necessary precondition for the recovery of his “sociable nature.”

Winthrop repeatedly described Christian love as a “ligament” that binds the Christian community into one body and mind. Love unites the parts and perfects the whole. It is the perfection of both the individual and the community. There would be no “I” in New England, only “we” in a covenantal relationship first with God and then with each other:

Whatsoever we did, or ought to have, done, when we lived in England, the same must we do, and more also, where we go. . . . [W]e must love brotherly without dissimulation, we must love one another with a pure heart fervently. We must bear one anothers burthens. We must not look only on our own things, but also on the things of our brethren. . . . We must be willing to abridge ourselves of our superfluities, for the supply of other's necessities. . . . We must delight in each other; make other's conditions our own; rejoice together, mourn together, labour and suffer together, always having before our eyes our commission and community in the work, as members of the same body.

Viewed metaphorically, Winthrop’s purpose in the sermon was not only to explain to his shipmates the transhistorical meaning of their passage from the Old to the New World (i.e., to establish a “City Upon a Hill”) but also to describe the spiritual and moral journey they were about to embark on from a state of selfishness to one of selflessness, from the self to the other, from the “I” to the “we.” The new Jerusalem was to be under a covenant with God and founded upon the virtues of obedience, love, and mutual affection. Winthrop’s sermon was a moral blueprint for the new society.

Winthrop was acutely aware that he and his fellow shipmates were about to conduct what they thought was the greatest social-religious experiment ever undertaken since the Apostles. They were establishing, as Winthrop famously said, “a City upon a Hill” that might serve as a model for the reformation of humankind and thus lay the basis for the Second Coming of Christ. It was critically important therefore that the residents of the New Jerusalem not only profess Christ’s true ethic but that they live it out its tenets every day. In Winthrop’s words, “That which the most in their Churches maintain as truth in profession only, we must bring into familiar and constant practise.”

Not since the communalistic way of life described by the Apostles in the Book of Acts had a group of individuals an opportunity to live out and fulfill Christ’s moral vision for man on earth.

Everything the Puritans did depended on the meaning and the practical implementation of the concept “charity.” By charity, Winthrop meant something spiritual rather than material; it meant first and foremost the sharing of love (understood as agape in the Greek and caritas in the Vulgate) more than the giving of alms, although it did promote and require the sharing of wealth. Winthrop was explicitly not using arguments that appealed to the “rational mind,” but his goal instead was to transform the soul of each member of the Puritan community “by framing these affections of love in the heart which will as naturally bring forth the other, as any cause doth produce the effect.”

The purpose of Winthrop’s redefinition of love and charity was to correct man’s post-Fall nature, which had liberated the self and self-love with it. Charity begins with the reformation and purification of the heart and soul in order to achieve the restoration of man’s true or original pre-Fall self.

In its turn, the reformation of the soul for Winthrop began with the assumption that sin was born of self-love, which is man’s inescapable post-Fall condition. Moral virtue for Winthrop therefore starts with self-denial and the overcoming of self-love. At the heart of Winthrop’s moral teaching is the belief that “every man is born with this principle in him to love and seek himself only, and thus a man continueth till Christ comes and takes possession of the soul and infuseth another principle, love to God and our brother.” Self-love separates and divides men and it pits them against each other. The goal is to reunite men through the body of Christ and then the body of God. Thus, it is the highest responsibility of those who have received the Lord’s saving grace to recover some semblance or their pre-Fall self because

the ground of love is an apprehension of some resemblance in the things loved to that which affects it. This is the cause why the Lord loves the creature, so far as it hath any of his Image in it; he loves his elect because they are like himself, he beholds them in his beloved son. . . . Thus it is between the members of Christ; each discerns, by the work of the Spirit, his own Image and resemblance in another, and therefore cannot but love him as he loves himself.

Winthrop believed that Christian love must be the foundation and necessary condition of Puritan society. As he noted in his sermon, Winthrop and his fellow Puritans viewed the “good of the whole” as the intermediate end of their community. He implored the members of his community to “have need of others” so that they “might be all knit more nearly together in the Bond of brotherly affection.” The moral glue that bound the Puritan community together was first God’s commandment (Leviticus, 19:18) and then Jesus’s (Matthew 22:39) to “love your neighbor as yourself,” which Winthrop calls a law of nature and which he says requires of men two things: “first, that every man afford his help to another in every want or distress,” and, secondly, “that he perform this out of the same affection which makes him careful of his own goods, according to that of our Savior, (Mathew) [7:12].” This form of love and charity requires of men that they satisfy “every want and distress” of other men.

What could this possibly mean?

Let us focus on the word “every.” What does it mean to say that men, or at least true Christians, must satisfy every want and need of other men or at least those in their community? At the very least, it meant that “if thy brother be in want and thou canst help him, thou needst not make doubt, what thou shouldst do; if thou lovest God thou must help him.”

Such a commandment, though, surely reverses moral cause-and-effect. The moral cause is need, want, or distress, and the necessary moral effect is the necessary action taken to satisfy the need. But how are need, want, and distress to be determined and by whom? And who shall enforce the commandment?

There can really be only three possible answers to this question: either the giver, receiver, or some third party must ultimately make this determination. Since the giver can’t know every man’s every need, want, or distress, he can’t—in the end—be the one determining how much he is morally obliged to “share.” Besides, the giver is too self-interested to fairly determine another’s need. Moral decision-making and action must be therefore removed from the person acting. This means that, at the very least, the receiver of said moral action determines what is owed to him by others, but since the receiver might not have the ability or power to enforce this commandment on the giver, it almost certainly means that a third party must play some role in enforcing the commandment.

Not surprisingly, Massachusetts Puritans established America’s first welfare state that was sometimes voluntary and enforced by systemic guilt and sometime involuntary and enforced by government coercion.

At the very least, Winthrop and the other political and church leaders in the Bay Colony were happily willing to fill that role. Quoting from Galatians (6:2-3,10), Winthrop advises his new neighbors that when they land in Massachusetts Bay, they must sometimes, when necessary, “give beyond their ability.” Sacrifice—the highest form of sacrifice—means that it should hurt, at least a little bit, otherwise it is not really a sacrifice. Winthrop also reminds his flock that after Adams’ fall and regeneracy, God commands men to not only love their neighbors as themselves but their enemies as well (Matthew 5:44), which presumably means their charity should extend to those who seek to harm them.

In sum, Christian love was, according to Winthrop, the sacrificial bond that united individuals into one whole—the body of Christ.

Winthrop’s sermon aboard the Arabella provided the moral inspiration for New England Puritans well into the early eighteenth century. (Indeed, one could argue that Winthrop’s message is and has been the Christian teaching to the present day.) New England’s leading intellectual lights all taught that Christian love and charity was the basis for their experiment in the New World.

Thomas Hooker (the founder of the Connecticut colony), John Cotton (minister of the First Church of Boston) and Cotton Mather (the grandson of John Cotton) were undoubtedly the three greatest theological minds of seventeenth-century New England, and all three men supported Winthrop’s understanding of Christian love and charity. After Winthrop’s “A Modell of Christian Charity,” the two most important sermons of the Puritan era were Hooker’s curiously titled “Heautonaparnumenos: or A Treatise of Self-Denial (1646)” and Cotton’s “The True Constitution of a Particular Visible Church (1642).” Mather’s Bonifacius, or Essays to Do Good (1710) represented a late-Puritan summing up of the Christian message of love and sacrifice.

Thomas Hooker, possibly the deepest thinker amongst all New England divines, understood that the greatest roadblock to experiencing and performing love for other men was man’s inherent, post-Fall selfishness. Adam’s Edenic nature prior to the Fall was imbued with love and there “was no such thing then in the world, as our Selfe, contradistinct from God,” but Adam’s disobedience alienated him not only from his Creator but from all other men as well. Post-Fall Adam and his descendants have, according to Hooker, become “Non ens [not being]” or “nothing” in the eyes of their Lord. The men or women who pursue their own self-interest to the exclusion of the needs of others are, in effect, non- or anti-human.

The first result of the Fall was Adam’s loss of his true and best self and the unveiling of his inauthentic and worst “self,” which in turn led to “that traitorous sin of Self-love” and “Self-will,” which means sin, the introduction of evil into the world, alienation from God, and, ultimately, “destruction.” (Surely, though, man’s false “self” was still a part of his original self, unless of course God implanted the selfish self into man after the Fall.) Hooker defined the characteristics of man’s corrupt self as “those Principles and Opinions which by Nature, now corrupted, are in every one, and incline him to establish his own Independencie of any other whatsoever, yea even of God Himself, and to crook every thing toward himself, so making himself the sole end of his thoughts, words and actions.” Stated more succinctly, Hooker defined the self as “our own Will to be or have any thing contrary to the Will of God.” All wickedness for Hooker stemmed from the post-Edenic self that had broken free from God’s commands.

Hooker sums up his antidote to the problem of the self and selfishness by quoting Matthew 16:24: “If any one will come after me, let him deny himself.” Self-denial (i.e., the rejection first of self-love and then ultimately of the self itself) is the fundamental Christian virtue and the source of all other virtues for Hooker; indeed, it is “the very Foundation of Christianity, yea the Grand Design of all Theology.” By self-denial, Hooker meant not just forgetting or denying one’s fallen “self,” it meant viewing one’s self as “not only Vile but, Nothing in our own eyes.” Self-denial is premised not just on self-loathing but on self-hatred. Indeed, we are, according to Hooker, “to Hate our selves and ours, when they are Contrary to Christ.” This kind of nihilistic self-hatred is the necessary pre-condition for self-denial and self-sacrifice, all of which leads to nothing or zero.

Christian self-denial means sacrifice; it means to “forsake all we have” as Christ did. The crucifixion and death of Jesus on the cross is for Hooker “as perfect a Pattern of this Precept” as exists. Christ’s sacrifice is the model, the highest expression of man’s moral ideal through which men can recover their lost relationship with God. The crucifixion is the reification of death as the highest earthly ideal for Christians.

And how does Hooker define self-denial in practice?

Connecticut’s theological lawgiver told his flock that “To Exalt, we must abase our selves: To be the First, we must become last of all: To be strong, we must become weak: To be wise, we must become Fools: To subdue our enemies, we must love them: To save our Lives, we must lose them, with many such like.” Hooker’s message was simple and clear: You are nothing unless and until you abdicate and deny your earthly self and submit to God’s will and give yourself over to Christ’s redemptive love, which becomes a kind of socialized Eucharist. Eternal damnation is the alternative. In a post-Fall world, self-denial is the necessary precondition for man’s positive duty, which is open-ended charity and love.

John Cotton, probably the greatest divine in Puritan Massachusetts, likewise shared Winthrop’s commitment to creating a community based on Christian love, charity, and self-sacrifice. The Puritan church and community were, as Cotton wrote in his “The True Constitution of a Particular Visible Church” (1642), a fellowship of saints who were called upon and united in “brotherly love . . . and the fruits of brotherly unity . . . brotherly equality . . . & brotherly communion.” By unity, Cotton meant a community “perfectly joined together in one mind and one judgment . . . not provoking or envying one another . . . but forbearing and forgiving . . . so far as we are come to walk together by the same rule.” And by brotherly equality, Cotton meant “preferring others” before oneself and “seeking one another’s welfare.” One wonders whether Karl Marx would have approved of New England’s Puritan community.

Two generations later, John Cotton’s grandson, Cotton Mather, explained in Bonifacius; An Essay Upon the Good how God’s divine and infinite love for man via Christ’s sacrifice provided the model for how men should love one another. Mather told his flock that they should “look upon themselves, as bound up in One Bundle of Love; and count themselves obliged, in very Close and Strong Bonds, to be Serviceable unto one another.” This meant that “if any one in the Society should fall into Affliction, all the rest should presently Study to Relieve and Support the Afflicted Person, in all the wayes imaginable.”

The Puritan doctrine of Christian love was more than just an abstract theory of their leading intellectuals and ministers. It was a living reality for the Puritans, or at least they attempted to live out the theory in practice.

In Dedham, Massachusetts, for instance, 125 founding villagers incorporated themselves via a written town covenant into a Christian quasi-commune in which they promised to each other that they would all live according to God’s laws and especially the commandment to love each other as they love themselves:

1. We whose names are hereunto subscribed, do in the fear and reverence of our almighty God, mutually and severally promise amongst ourselves and each to other, to profess and practice one faith, according to that most perfect rule, the foundation whereof is everlasting love.

Love for God and love for their fellow villagers defined the moral foundation for this utopian Christian community. This love requires of all covenanting community members that they all first purge themselves of their self-love and then transform their selfish desires into a love for their fellow men. The covenant bound each man to all the others in a pledge taken in the presence of God to practice Christian love with each other in their lives day to day. This “most perfect rule” bound the community together and was moral foundation for this community founded on Christian love.

It is important to note, however, that such love can only be sustained amongst church members and no one else, which meant

2. That we shall by all means labor to keep off from us, all such as are contrary minded; and receive only such unto us, as be such, as may be probably of one heart with us; as that we either know, or may well and truly be informed to walk in a peaceable conversation with all meekness of spirit, for the edification of each other in the knowledge and faith of the Lord Jesus; and the mutual encouragement unto all temporal comforts in all things; seeking the good of each other, of all which may be derived true peace.

Notice that the Puritans’ brand of Christian love was not a universal expression of love for all men or even for Christians generally speaking, but it was limited to those of the same village and the local congregational church. All others—the “contrary minded”—were to be excluded from this communion of “one heart.” It’s love by exclusion. Not only was the Puritans’ Christian love limited to Puritans, it was limited to one’s own town or congregation.

Puritan community members were to walk together in “mutual encouragement unto all temporal comforts in all things; seeking the good of each other,” which suggests that they were, to one degree or another, to live according to the spirit of the disciples in the Book of Acts. (One does wonder why the Puritans limited their love to their fellow congregants only, and one also wonders whether Christ’s teaching was meant to be as parochial as the Puritans’ understanding or whether it was more universal in scope.)

In the end, though, true Christian love—voluntary love for one’s neighbors—was not possible without a little help from others. Christian love almost always requires help from either third parties (e.g., friends, neighbors, colleagues, etc.) or from government. Disagreements, including disagreements over how much one owes others in terms of love, were to be resolved initially by a committee of neighbors, townspeople, or church members, who played the role of mediators, and who were to use the Golden Rule as their guiding principle:

3. That if at any time difference shall arise between parties of our said town, that then such party and parties, shall presently refer all such difference unto one, two, or three others of our said society, to be fully accorded and determined, without any further delay if it possibly may be.

But of course, such voluntary committees sometimes needed extra support from coercive local governments in the pursuit of a unified community built on the principle of Christian love. Sometimes Christian love and charity are insufficient to supply the needs and wants of those who are needy and wanting, which means Christian love and charity need a coercive backstop in the form of government-mandated redistribution:

4. That every man that . . . shall have lots [land] in our town, shall pay his share in all such rates of money and charges as shall be imposed upon him . . . in proportion with other men, as also become freely subject unto all such orders and constitutions, as shall be necessarily had or made, now at any time hereafter from this day forward, as well for loving and comfortable society in our said town, as also for the prosperous and thriving condition of our said fellowship, especially respecting the fear of God, in which we desire to begin and continue, whatsoever we shall by his loving favor take in hand.

Implied in this fourth clause is the assumption that not all Christians could embody Christian love all the time, particularly when it comes to each man paying “his share,” which meant that they needed additional guidance, motivation, and direction from “orders and constitutions” by which they meant the coercive force of local government.

This problem is and always has been endemic to the Christian ethic. Because selfless love cuts against the grain of human nature, it requires added incentives and support. In other words, it must be enforced. Those incentives and that support most often come in the form of guilt (both personal and communal) and the threat of eternal damnation, and when guilt and hell do not work a little helping hand from the State helps to incentivize men to love their neighbor as they love themselves.

Conclusion

At the heart of the Puritan-Christian moral teaching was and is the idea that man must sacrifice his life for the sake of others, for the sake of God, for the sake of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, and for the sake of redemption. (Are acts for the sake of redemption self-interested?)

Not only is this Christianity’s moral ideal, but it is also God’s commandment to man. To reject this teaching or to act otherwise would be, of course, a sin, which is why seventeenth-century Puritans believed that there cannot be a separation of religion from government, church from State, and ethics from politics. The union of Bible and State was necessary fulfill Christ’s command to love thy neighbor as thyself. The Puritan mind assumed that man’s spiritual life was synonymous with his communal life, and this is why the Puritans were willing to use the coercive force of the State to make men love one another.

One obvious problem with the Christian ethic is that it does not work. The Puritans tried and failed, and many other Christian communities built on Christian love have been tried and failed.

The problem, of course, is that Christian love asks of man that which is impossible. History and the human condition demonstrate, including the history of the American Puritans, that Jesus’s core ethical teaching is not sustainable psychologically, morally, politically, or economically because it runs counter to human nature and thus to the morality necessary to sustain both human life and human morality. This is why the Puritan experiment was bound to fail, which it did. It could not sustain itself over time. Like the socialist ethic, the Christian ethic leads to envy, resentment, conflict, and the use of guilt and coercion.

By the early decades of the eighteenth century, a new moral and political philosophy began to seep into the colonies. This new moral and political ideal moved rapidly away from the Puritan ideal. It assumed that men could live freely with a minimum laws, police, judges, and magistrates telling them how to live and whom to love. This assumption held that free individuals had a moral right to pursue their self-interested goals and ends, and it further developed into the Jeffersonian ideal that the best government leaves men alone and governs as little as possible.

To believe that men are born with inalienable rights to life (their life), to liberty (their liberty), to property (their property) and to the pursuit of happiness (their happiness) would have been anathema to the Puritan worldview. The new moral and political philosophy that came out of the American Revolution and the founding of the United States held that the best government is one that is little more than an umpire protecting the unalienable right of men to pursue their individual self-interest free from internal and external criminals and free from the guilt of not serving others.

I am making the audio file available to everyone this week.

**A reminder to readers: please know that I do not use footnotes or citations in my Substack essays. I do, however, attempt to identify the author of all quotations. All of the quotations and general references that I use are fully documented in my personal drafts, which will be made public on demand or when I publish these essays in book form.

https://youtu.be/VUYooprteeU

Podcast audio:

In this episode of The Ayn Rand Institute Podcast, Onkar Ghate and Agustina Vergara Cid analyze how the Trump administration’s immigration policy has escalated attacks on due process, legal immigration, and the broader American system of government.

(Since the recording of this podcast, Rümeysa Öztürk has been granted bail by a federal judge and released after more than six weeks in detention.)

Among the topics covered:

* How the Trump administration has ramped up mass deportations as a show of power;

* The chilling, unconstitutional actions targeting legal immigration;

* How Trump’s actions build on a long history of corrupt immigration laws and enforcement;

* How the attack on due process aims at scaring immigrants into self-deporting;

* How the unchecked abuse of executive powers threatens the American system of government.

Recommended in this podcast is the previous podcast episode on “What Would Mass Deportations Mean for Freedom in America?”

The podcast was recorded on May 7, 2025 and posted on May 14, 2025. Listen and subscribe wherever you get your podcasts. Watch archived podcasts here.

Download video: https://www.youtube.com/embed/VUYooprteeU

Download audio: https://media.blubrry.com/new_ideal_ari/content.blubrry.com/new_ideal_ari/20250514_Governments-Display-of-Power-Through-Immigration-Enforcement.mp3

Capitalism protects an individual’s right to be free from tariffs and military aggression.

The post Ayn Rand Knew Free Trade and National Security Were Allies appeared first on New Ideal - Reason | Individualism | Capitalism.