WASHINGTON, D.C. — Global tensions over tariffs continued to rise amid the ongoing trade war, as the White House announced that General Tso's Chicken would be renamed General Don's Oriental Chicky Nugs.

WASHINGTON, D.C. — Global tensions over tariffs continued to rise amid the ongoing trade war, as the White House announced that General Tso's Chicken would be renamed General Don's Oriental Chicky Nugs.

Is it really “efficiency” if you have to run your dishwasher twice to get your dishes clean?

President Donald Trump’s tariff agenda exhibits no signs of a popular mandate. Recent polling found that 61 percent of the public believe raising tariffs will hurt average Americans, compared to just fourteen percent who see them as helpful. Seventy-six percent expect tariffs will produce increased prices at the store. Clear majorities also oppose Trump’s specific tariff measures against Canada and Mexico. Mainstream economists have panned the administration’s claims that their tariff program will “substantially reduce the US trade deficit.” Unlike past tariffs, which usually drew their support from special interest groups in the beneficiary industry, there does not even appear to be a concerted lobbying effort behind Trump’s current agenda.

The economy has also delivered a harsh verdict on the White House trade agenda. In the past month, a see-saw of stock-market nosedives and recoveries with each new tariff announcement has been replaced by economic free-fall. As of this writing, the Dow Jones has lost more than ten percent of its value since Trump’s inauguration in January and the S&P 500 has lost closer to fifteen percent. Tariff uncertainty has obliterated US consumer sentiment and international supply chains are preparing for a tariff-induced shock. The market dislikes tariffs in general, but it also abhors the uncertainty created by this haphazard roll-out.

At the most basic level, the president’s stubborn attachment to tariffs stems from an ideological belief. Trump is a self-described “tariff man” after all, and espousal of protectionism may be the most stable component of his political belief system over the past forty years. Yet Trump’s current tariff policy is also erratic, ill-defined, and incoherent. Its justification swings between the mutually exclusive goals of protecting industries through import-exclusion from abroad on one hand, and raising tax revenue from the very same imports as part of a scheme to replace income tax on the other.

....I am a Tariff Man. When people or countries come in to raid the great wealth of our Nation, I want them to pay for the privilege of doing so. It will always be the best way to max out our economic power. We are right now taking in $billions in Tariffs. MAKE AMERICA RICH AGAIN

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) December 4, 2018

When Trump bluffs then retracts a tariff threat to attain diplomatic concessions, tariffs are merely a negotiating device. When he pulls the tariff trigger on the same nation a few days later, we’re told that it’s to address a national-security “emergency” on the border or part of a plan to somehow offset Chinese steel production by taxing Canadian steel. When the markets crash, it’s all part of an elaborate four-dimensional chess game to restructure the global economy. Administration talking points about the dangers of a tariff-induced recession change by the hour, ranging from denying any threat of economic turmoil to insinuating that some purposeful economic “reset” of the global trading system is afoot.

The resulting volatility of conflicting policies and messages bears little resemblance to the steel tariffs of Trump’s first term. Those burdened consumers with higher prices and cost the country about 142,000 jobs net, but they were also constrained to a few well-defined foreign-policy objectives. The implementation this time around has been pure chaos.

This confusion is the result of an ideological battle being fought inside the White House. Although Trump assembled an economic team of like-minded “tariff men” to enact his policies, his advisers seem to be at odds over what the tariffs they favour are supposed to achieve. The chaotic implementation of the past two months reflects their competing goals, which include classical protectionism, revenue generation, and a sweeping scheme to devalue the dollar and “reset” the international economy. Instead of forming a cohesive tariff agenda, they vie for the president’s ear and lead him down conflicting paths.

At present, there appear to be about five different tariff camps within the Trump administration. Since the economics profession overwhelmingly rejects tariffs, almost all of Trump’s “tariff men” hail from the fringes of the discipline. But these peripheral perspectives do not agree with each other as a brief survey of the tariff landscape will reveal.

This view best approximates Trump’s own beliefs, as well as those of his senior trade adviser Peter Navarro. Classical protectionism holds that international trade is a zero-sum game determined by maintaining a surplus of exports to imports. Adherents of this view in the White House see trade deficits as evidence that trading arrangements are rigged to disadvantage America. Tariffs, then, are the policy mechanism employed to reverse this alleged imbalance by protecting domestic manufacturers and penalising their foreign competitors with a tax.

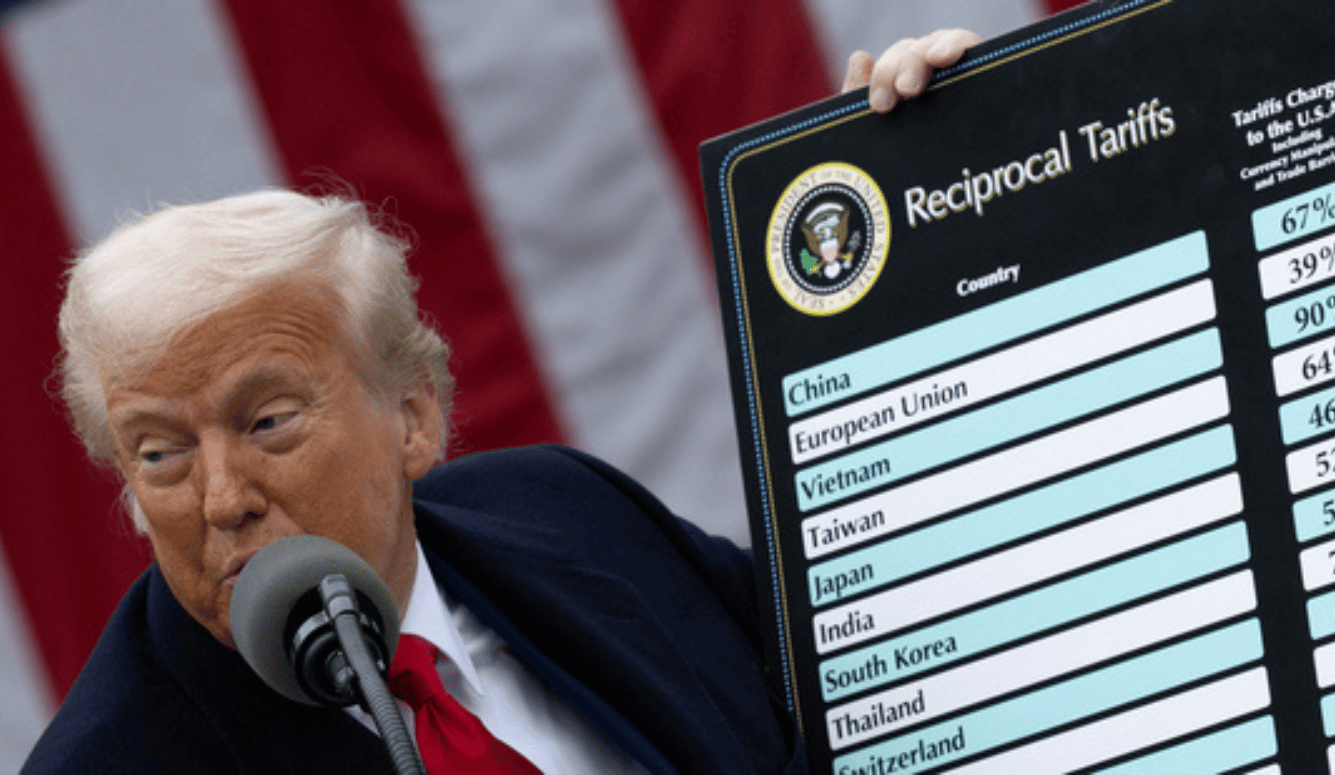

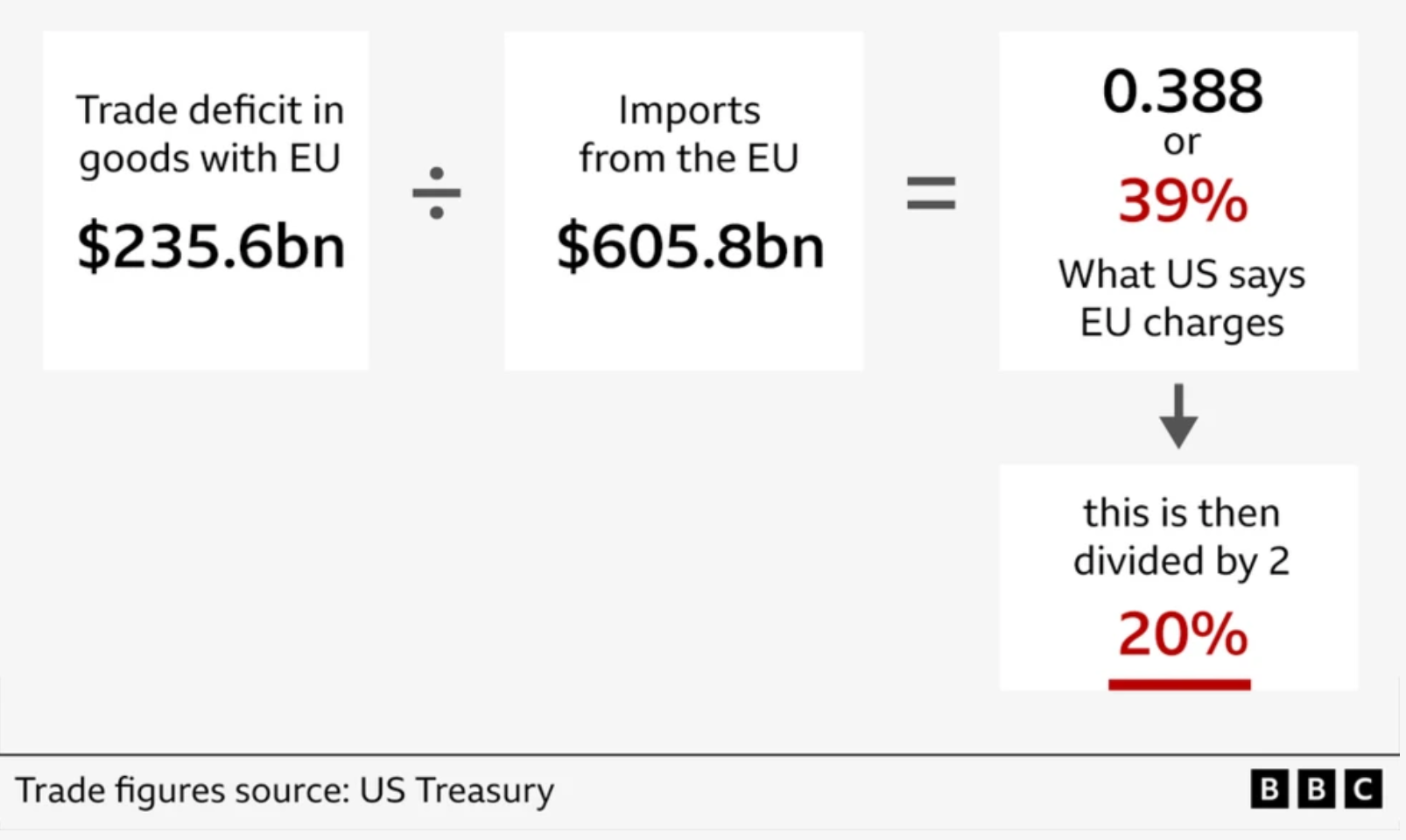

Protectionism of this type is premised on a misunderstanding of a basic accounting identity. Trade-deficit hawks take a measure of expenditures on foreign goods and services without noticing the corresponding inflows of foreign investment. They also incorrectly assume that tariffs mainly harm foreign producers by slapping a punitive tax on their goods. This was the premise behind Trump’s widely derided “reciprocity formula,” which imposed astronomical tariffs on any country with which the United States has a bilateral trade deficit (in addition to a ten percent minimum rate for those with which it has a surplus).

The Trump administration’s “reciprocity formula” is an exercise in economic alchemy informed by stunning economic incompetence and no intelligible underlying principle.

This formula mistakes the existence of a trade deficit for external trade barriers, and then calculates a meaningless “rate” by dividing the net difference between exports and imports by the value of imports and halving the result. It is an exercise in economic alchemy informed by stunning economic incompetence and no intelligible underlying principle. Navarro allegedly devised it himself and has since become its leading exponent in the media, revealing in the process that he does not understand grade-school arithmetic, let alone trade economics.

The burdens of Navarro’s statistical contrivance will nonetheless impose profound and adverse effects on most Americans. Contrary to the classical protectionists’ claims, the costs of a tariff are inevitably passed on to consumers—either through price increases used to absorb the tax itself or by importers shifting procurement to “protected” domestic firms, which then raise their prices to a level that corresponds with the tax.

And far from reversing trade deficits, tariffs of this type ultimately impose self-defeating penalties on US exporters. First, because exporters are price-takers on a global market and must therefore absorb any increased costs to their raw material inputs caused by tariffs. And second, because tariffs tend to trigger retaliatory trade wars abroad, in which other countries target US exporters with punitive levies, thereby cutting them off from the international market.

Although neo-mercantilists are closely related to the classical protectionists in their trade-deficit focus, they take a historical approach to tariff advocacy. Trump himself has adopted some of these arguments through his peculiar rehabilitation of William McKinley, the namesake of a highly protectionist tariff in 1890, and then US president from 1897 to 1901. Other neo-mercantilist voices in the administration include vice president J.D. Vance and Trump’s domestic-policy adviser Wells King, a former Vance Senate staffer who served as research director for the tariff-advocacy think tank American Compass. Trump’s secretary of state Marco Rubio has also flirted with this viewpoint during his Senate career.

Neo-mercantilists credit the United States’ economic development to an obscure 19th-century tariff ideology known as the “American System.” First proposed by Kentucky senator Henry Clay in 1824, the American System aimed to achieve an economic “harmonisation” of the national economy through a suite of tariffs, regulations, and government subsidies. The gist of the theory holds that government planning can align the domestic producers of raw materials with domestic manufacturers, obviating the need for foreign imports and—allegedly—creating a self-reliant and quasi-autarkic internal economy.

Clay’s program had many adherents in the 19th century, although Thomas Jefferson and James Madison each lived long enough to denounce it as a betrayal of America’s founding principles. It attained the upper hand for several decades after the Civil War, and heavily influenced US tariff policy until World War II. The American System was the undergirding ideology behind the disastrous Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930. Faced with the 1929 stock-market crash, American System adherents prescribed tariffs as a “stimulus” package that would insulate the country from the ravages of the global downturn. Instead, it caused a retaliatory collapse in global trade and helped to supercharge the recessionary headwinds, contributing to a decade-long Great Depression. The post-World War II shift toward free trade, bemoaned by tariff advocates today, came about in direct response to the failures of Smoot-Hawley.

Today’s neo-mercantilists downplay this dubious legacy and claim—against all empirical evidence—that tariffs actually jump-started American industrialisation in the late 19th century. A persistent air of resentful conspiracism surrounds contemporary adherents of the American System, evident in Trump’s rhetoric about other countries “ripping America off” with free trade and convoluted tales about a largely imaginary drug-smuggling ring at the northern border with Canada. Allegations like these are a longstanding feature of these debates, traceable to 19th-century Anglophobia and revived in the 20th century by Pat Buchanan’s economic populism in the 1990s and the histrionic paranoia of the Lyndon LaRouche political cult. (The LaRouchies maintained that protective tariffs were necessary to insulate the American economy from a British-led international plot to flood the US with opiates.)

Today’s neo-mercantilists believe that 20th-century trade liberalisation was the product of an international conspiracy designed to subordinate the American economy, and that the economics profession was in on the plot. Mainstream economics, they contend, is controlled by free-trade dogmatists who oppose tariffs as a matter of religious devotion. These and similar arguments have become a mainstay for American Compass’s Oren Cass, who proselytises his tariff message in seminars for Capitol Hill staffers and has taken a leading role in defending the Trump administration’s “liberation day” tariff scheme in the media.

In terms of day-to-day influence, this peculiar faction is not designing the administration’s rates and policies. Navarro’s contrived reciprocity formula—dressed up in Greek letters and misrepresented citations from economics journals—is a beacon of numeracy when compared to the arguments of the neo-mercantilists. The neo-mercantilists have, however, supplied Trump with an alternative epistemic framework with which to justify dismissal of the overwhelming majority of professional economists opposed to the president’s tariff policies.

Elsewhere in the administration, another faction of Trump’s “tariff men” has enlisted a different historical argument to their cause. They note that prior to the adoption of the federal income tax in 1913, tariffs provided the lion’s share of federal tax revenue. To tax replacers, tariffs represent an untapped revenue source that will eventually allow for the abolition of the Internal Revenue Service and the restoration of this 19th-century tax system. Commerce secretary Howard Lutnick has emerged as a leading proponent of the tax-swap argument (although he adopts arguments from the other camps as well), and Trump has made use of the same rhetoric. The president’s inaugural address proposed replacing the IRS with an “External Revenue Service,” which signals that he shares this view, as does Lutnick’s more recent proposal to eliminate income taxes for those making under US$150,000.

There are several problems with the income-tax swap argument. Although tariffs did at one time fund the federal government, this system also reflected 19th-century levels of federal expenditure. When translated to the present day, the mathematics of a tariff swap simply do not add up. Federal income taxes currently raise about US$2.5 trillion dollars a year, whereas the total value of imported goods is about US$3 trillion. That implies we would need a national tariff of 83 percent on all imports to make up the difference, and only under the unrealistic assumption that trade volume would not diminish because of the tax penalty.

Here we find the second problem with the tax-swap strategy. To raise any revenue from tariffs, imported goods must physically cross the border so that a tax is collected. This puts the tax replacers at direct odds with the classical protectionist and neo-mercantilist camps, which aim to obstruct importation and redirect consumption towards domestic firms at higher prices. In simpler terms, tariffs can be used for maximising revenue or for heavy protection but not both. Nineteenth-century politicians understood this tradeoff, and accordingly held specific tariff rates below their protectionist optimum to ensure a sufficient revenue yield from imports. Today’s income-tax replacers do not appear to have absorbed this historical lesson, leaving Lutnick in a state of perpetual vacillation between the antithetical goals of delivering protection to industries and a revenue replacement for the income tax at the same time.

A fourth faction within the administration appears to view tariffs as a negotiating tool for achieving strategic objectives in the international arena. By using tariffs to threaten allies and adversaries alike, Trump aims to coax both into an array of policy reforms in exchange for rescinding those threats: immigration and drug enforcement at the northern and southern borders, increased expenditures on NATO and other military obligations, and removal of tariff and tax barriers employed against the United States in exchange for “reciprocity.” Tariffs are even being used to lean on countries that trade with hostile regimes like Venezuela. By implication, if other countries accede to tariff threats by changing their policies, they can escape the punitive threat of a 25 percent levy on their imports into the United States. And if they agree to reciprocal reductions in existing tariffs, the United States may even reward them with preferential trading-partner status.

National Economic Council director Kevin Hassett has emerged as one of the main spokespersons for tariff reciprocity, and a number of Trump’s own statements and policy reversals have implied this carrot-and-stick approach. To his credit, Hassett appears to be the only senior official who regularly exhibits some scepticism about ideological protectionism. In recent weeks, he has argued that the White House is seeking a freer trading system in the long run, with tariffs serving as an inducement for foreign countries to remove unfair barriers against the United States.

There are two problems with this approach. First, the United States’ tariff rates and non-tariff barriers are already on the higher end when compared to other developed economies. The United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, and the European Union all ranked higher than the United States on most indexes of trade liberalisation before Trump took office. True reciprocal negotiation would therefore require the United States to lower its own tariffs and trade barriers to match those of its major trading partners.

Second, while successful reciprocal reduction achieved through negotiating bluffs would be the least harmful economic outcome of the current tariff war, for the negotiating strategy to work, the tariff threat must be a credible bluff. Trump’s strategy is essentially to create an international game of chicken in the hope that other countries blink and accede to his demands. If they don’t, the world is trapped in a race to the bottom and spiralling retaliatory measures, just as the US is currently experiencing with Canada. And once the bluff has been successfully used, it is no longer effective as a tactic. The see-saw effect of tariff-policy reversals also undermines the White House’s negotiating position by creating a moving target of reciprocal objectives and degrading trust in the United States’ willingness to honour its word on a previous settlement.

Unfortunately, it appears that Trump has already expended his negotiating advantage on tariffs during his first two months in office, with little to show in return but a significant loss of trust as he reneged on existing tariff pauses and decided to proceed with additional tariff threats. He played all of his cards in the first two months of his administration, proceeded with his “liberation day” tariffs anyway, and is now met with justifiable distrust by the rest of the world.

The negotiating-bluff approach also places its proponents in tension with the protectionist and revenue factions in the administration. A threatened tariff cannot achieve either goal if it is rescinded before it takes effect, and a true reciprocal reduction would require the United States to give up some of its own existing tariff and non-tariff barriers on goods from other countries.

Trade rebalancers are arguably the most dangerous tariff faction in the White House, on account of the sweeping designs they propose to achieve with Trump’s tariff agenda. This newly emergent faction wants to use tariffs as a means of restructuring the international economy and international exchange system. The leading proponent of this approach is Stephen Miran, the chair of Trump’s Council of Economic Advisers. Miran authored a “User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System” shortly before his appointment to that role, and some have argued that it is the blueprint for the administration’s sweeping tariff agenda. Trump’s own rhetoric has hinted at similar designs, such as the “liberation day” moniker he affixed to his 2 April announcement.

Like classical protectionists, rebalancers dislike trade deficits but they disagree about their source. Rebalancers believe deficits are caused by a “persistent dollar overvaluation” in the international economy due to the US dollar’s de facto status as the world’s reserve currency. Miran has accordingly espoused a “Mar-a-Lago Accord” with the intentional aim of “rebalancing” trade through a managed devaluation of the dollar under a multilateral currency-pegging agreement.

Miran’s proposal creates a conundrum for the classical protectionists. Under a floating exchange system, a tariff will generally strengthen the dollar’s position against other tariffed countries and thereby obviate its purported trade-balancing effects. To get around this obstacle, rebalancers believe they can use additional tariff threats and reciprocity offers to coax smaller countries into implementing a preferential currency peg to the US dollar. They believe this would allow the simultaneous pursuit of aggressive tariffs for protective and revenue purposes—perhaps as high as a twenty percent “benchmark” tariff, according to Miran’s proposal—while also managing a devaluation of the dollar’s position, and overlaying it with an induced swap of current short-term US Treasury holdings by other countries for century-long bonds.

This fanciful rebalancing scheme is almost certainly unworkable in practice as it presumes a level of international buy-in that does not exist. Even as theory, the scheme treats the international economy as a closed loop where obvious tariff-induced pressures on prices can be offset by a carefully executed currency-manipulation scheme and a fair amount of wishful thinking.

In a rambling speech after Trump’s “liberation day” announcement, Miran declared that the economic consensus against tariffs is “wrong.” He offered no evidence for this assertion beyond reiterating his own heterodox opinions as if they were settled fact. Instead, the CEA chairman announced that other countries could only obtain relief from Trump’s tariff regime by acquiescing to a list of extortionary demands: they can “accept the tariffs” and pay them; they “can stop unfair and harmful trading practices,” as alleged but seldom elaborated upon by the Trump administration; they can purchase weapons and other military equipment from the United States, as a form of reparations for partaking in international trade under an American security umbrella; their governments can relocate factories to the United States, essentially adopting economic central planning; and foreign governments “could simply write checks to Treasury that help us finance global public goods.” It remains unclear how any of these threat-induced concessions would achieve the Trump administration’s goals, or if Trump would even honour an attempt to meet them.

Trade rebalancing is essentially Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) for the tariff-fundamentalist Right, and Miran is quickly becoming their Stephanie Kelton. And as with the MMT movement that led the Biden administration into the worst inflationary crisis in forty years, many of the rebalancer arguments rest upon a misunderstanding of basic economic concepts. For example, the authors of the paper that Miran uses for his twenty percent “benchmark” tariff have publicly accused him of misusing their work.

More recently, Miran gave a heterodox defence of tariffs on Bloomberg that suggested he misunderstands basic concepts such as the effects of price elasticity on tax incidence. He incorrectly believes that foreign nations incur the bulk of a tariff’s burden, in contrast with well-known passthrough effects that saddle US consumers and especially US exporters with higher prices. But just like MMT’s money-printing fantasies on the Left, immense economic damage could occur if the Trump administration attempted to intentionally devalue the dollar in earnest through tariff-bullying and coerced currency pegs.

While the USTR tariff calculator cites the findings from Cavallo, Gopinath, Neiman & Tang (2021) it is not entirely clear how they use our findings. Based on our research, the elasticity of import prices with respect to tariffs is closer to 1. If that figure were used instead of… https://t.co/8xs9ojm9Ex

— Alberto Cavallo (@albertocavallo) April 4, 2025

At present, it is unclear which of these five tariff factions has the upper hand in the White House. And therein lies the problem. Each of the five competing tariff ideologies is economically perilous on its own, albeit in slightly different ways. Classical protectionism could trigger a retaliatory trade war. A tax-swap strategy could backfire as its revenue yield underperforms, meaning Americans would be double-taxed with new tariffs and the existing federal income-tax system. If taken to its extreme, a tariff-based currency devaluation scheme, executed through the hapless political tools and erratic style of the Trump White House to date, could trigger a global recession. And the negotiating bluffs of the last few months appear to have already run their course, leaving US credibility in tatters abroad.

Another complication is starting to emerge from dissent within Trump’s own ranks. Amid the ongoing stock-market crash precipitated by Trump’s “liberation day” tariffs, a public feud has erupted between Peter Navarro and Trump’s DOGE adviser Elon Musk. In a post on X, Musk accused Navarro of incompetence and suggested that his own goals include the elimination of trade barriers with several of our major trading powers. So long as Navarro continues to have the president’s ear, it will strain relations with the administration’s chief waste-cutter.

Navarro is truly a moron. What he says here is demonstrably false.

— Elon Musk (@elonmusk) April 8, 2025

The antics of the “tariff men” are beginning to imperil other policy priorities, such as deficit reduction. Future objectives such as renewing the income-tax cuts of Trump’s first term will likely face similar headwinds as long as the trade wars continue to dominate the president’s economic agenda. But there’s another lesson to be learned from the assortment of competing goals and competing tariff men in Trump’s orbit. When pursued together, their conflicting objectives become an incoherent mess of contradictory policies and chaotic vacillation. The result is tariff uncertainty and tariff chaos with a commensurate toll on the health of the US economy.

Sorry, no, we can't avoid talking about bloody tariffs and trade deficits again.

XKCD explains it all very simply ...

|

| [Hat tip Duncan B.] |