Starring Chris Pratt, Rebecca Ferguson, and Kali Reis

Written by Marco van Belle

Distributed by Amazon MGM Studios

Rated PG-13 for violence, bloody images, some strong language, drug content, and teen smoking.

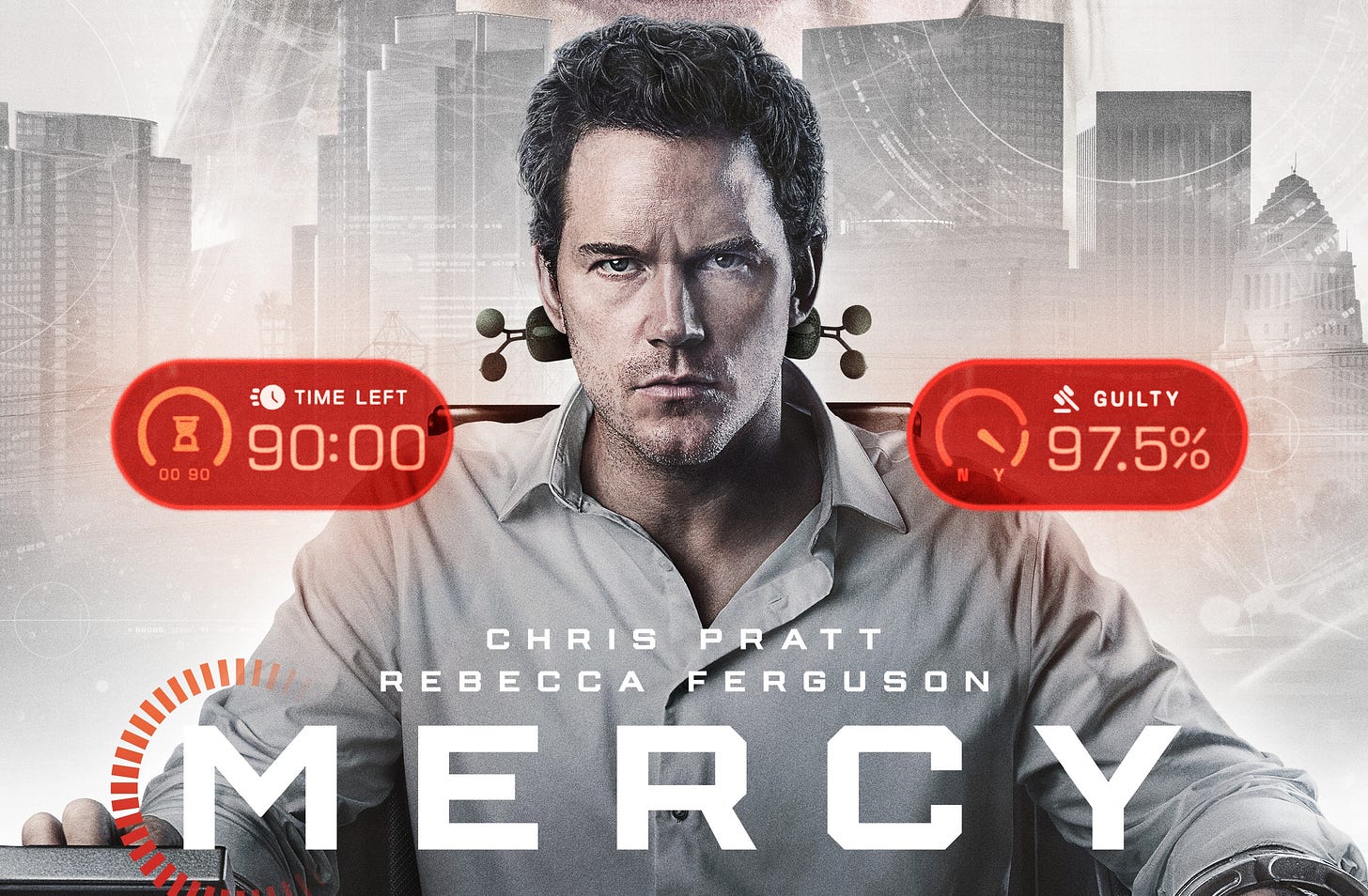

Imagine that you are wrongly accused of murdering someone close to you. You don’t have an advocate to defend you or a jury to convince of your innocence. Rather, you’re sealed in a room with no access to the outside and given a mere ninety minutes in which to argue your case to an AI that has already calculated with a supposed 97.5 percent probability that you have committed the crime.1 If you can’t get that percentage below ninety-two, you’re dead.

This is the dystopian premise of the new thriller Mercy, set in Los Angeles in 2029. It follows the “trial” of LAPD detective Chris Raven (Chris Pratt), who must fight for his life after being accused of murdering his wife. His opponent is Maddox (Rebecca Ferguson), the AI “judge, jury, and executioner” created as part of the Mercy Program, which Raven advocated and spearheaded. His one hope is the vast array of surveillance data to which Maddox has access.

Many viewers and critics have approached Mercy as a warning about how AI and intrusive government surveillance could combine to destroy privacy. Although that risk is conveyed by the film’s setting—a world in which the LAPD, Maddox, and the accused (for the duration of the trial) have access to everything recorded by almost every internet-connected mobile device and camera in the city—that isn’t the film’s fundamental point. Rather, a hint of its main idea lies in the context that gave rise to the LAPD’s decision to create the Mercy Program: an out-of-control violent crime epidemic. Raven and the city’s officials argued that for the city’s residents to be able to live in peace, a fast, efficient, and impartial method of capturing, prosecuting, and executing violent criminals was necessary.

Raven knows—or at least is completely convinced—that he’s innocent, and yet he finds himself judged guilty by a system he thought was infallible. After seeing the evidence, he begins to wonder whether he may have committed the crime and then forgotten through alcohol-induced amnesia. It’s only when he resolves to dive deeper into the mystery and use his remaining time to find the truth that he starts to uncover evidence that innocent people may have been put in front of Mercy and later executed. Raven comes to realize that the Mercy Program has bypassed citizens’ essential right to a fair, public hearing in the name of cutting crime levels, forcing suspected criminals into a “trial” in which Maddox’s “judgment” is supreme.

It becomes clear that Maddox lacks intuition—the human ability to subconsciously combine our experiences (including those we can’t consciously recall), emotions, and value judgments—which can enable us to spot signs that evidence may be misleading. Contrary to Maddox’s expectations, his rigorous exploration of seemingly unrelated evidence, guided by intuition, ultimately helps him uncover the surprising truth. At the end of the film, Raven—having discovered that both Maddox’s errors and human mishandling of evidence have led to unjust executions—remarks that both humans and AIs are capable of error. Although Maddox appears, unlike a human, to exercise flawless logic, she can miss signs and wrongly attribute importance to evidence because she lacks both a subconscious mind and a capacity to integrate emotions and value judgments with her logic.

Many reviewers have criticized Mercy for not exploring the rectitude of using AI in a criminal justice process and have called it a pro-AI film, but it is by exploring Maddox’s lack of intuition (her inability to experience “gut feelings”) that the film reaches its core idea: Whatever level of crime a society may be facing, a decision over a person’s life and freedom cannot be entrusted to a single judge. Rather, that person must have the means to defend himself to other human beings in a context that is open to scrutiny and challenge. The film conveys this idea successfully thanks to its captivating mystery and series of plot twists. It also delivers a compelling character arc for Raven during the film’s hundred-minute run time. He goes from a grieving alcoholic to a character who heroically struggles to uncover the truth about the previous Mercy Program trials and prioritizes justice over his loyalty to his friends in the process.

The fact that the film is interesting and entertaining is reflected in its audience reception, which contrasts dramatically with its critical ratings. At the time of writing, it has an 81 percent audience score on Rotten Tomatoes against a 20 percent critic score.2 The negative reviews that dominate mainstream-press articles about the film focus heavily on its relatively low budget, resulting in a limited range of locations (most of the story takes place in the Mercy Program’s chambers, with the events under examination displayed through a holographic interface) and a reliance on CGI for action sequences. They also deride the choice of Pratt for lead actor and the film’s limited exploration of Raven’s marriage and alcohol issues.3 Some of these are reasonable things to mention in a review, although Pratt was much better than one might expect from some of his past roles, and Raven’s backstory added value to the main storyline. The fundamental problem with these reviews, however, is that they fail to engage with the film’s core moral idea.

If there’s anything substantive to criticize about Mercy, it’s that despite her lack of intuition, Maddox acts too much like a human being. It’s realistic that by 2029, AIs will have become terrifyingly believable when imitating human emotion and mannerisms; and for much of the film, Ferguson’s performance believably captures an AI doing a very close approximation of human behavior. But it’s clear toward the end that Maddox is not merely imitating: “She” experiences doubt and chooses to act against her programming out of what appears to be emotion—sympathy for Raven’s evident heartbreak over his wife’s death and his frustration at knowing he’s innocent, as well as dismay over realizing that she’s made errors. She is shocked that Raven’s “gut feeling” about an aspect of the case turns out to be correct despite apparently contrary evidence, and she recognizes this as a sign that the way she evaluates cases is flawed and that humans possess an ability she lacks. She does not understand that the human brain can integrate evidence and spot patterns subconsciously as well as consciously—and this flaw is why she is unable to fairly judge those who are put in front of her despite her extensive resources and processing capabilities.

Although this portrayal leans into the common misconception of the technology we now call “AI” as potentially sentient and conscious (which there is no reason to believe it is or is likely to become), it does not impede the film’s ability to deliver both an exciting story and a relevant idea about the nature and importance of a proper justice process. Mercy is a far better film than its critical reception suggests, and anyone who values an entertaining story conveying a life-serving theme about justice is sure to enjoy it.

This article appears in the Spring 2026 issue of The Objective Standard.

The standard for how Maddox quantifies this probability is not made clear.

“Mercy,” Rotten Tomatoes, https://www.rottentomatoes.com/m/mercy_2026 (accessed February 9, 2026).

Clarisse Loughrey, “Mercy Review—An AI Judge Decides Chris Pratt’s Fate in This Absolutely Dismal Dystopian Dreck,” The Independent, January 22, 2026, https://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/films/reviews/mercy-movie-review-chris-pratt-rebecca-ferguson-b2905313.html; Maxance Vincent, “‘Mercy’ Review: The Spirit of Albert Pyun Lives On in This Horrendous Knockoff,” FilmSpeak, January 23, 2026, https://filmspeak.net/movie-reviews/2026/1/23/mercy-review-the-spirit-of-albert-pyun-lives-on-in-this-horrendous-minority-report-knockoff; Wilson Chapman, “‘Mercy’ Review: This Movie about Chris Pratt Sitting in a Chair Is the Platonic Ideal of a January Release,” IndieWire, January 21, 2026, https://www.indiewire.com/criticism/movies/mercy-chris-pratt-movie-review-1235173548.

Arka Serezh is the founder of Gondor Industries, a company pioneering robotically cut stone for architecture and sculpture. I interviewed him at the premises of The Stonemasonry Company in Stamford, England, where he has established his first robotic stonemasonry operation.

Thomas Walker-Werth: How did you get into stone masonry? When did you realize that this is something you’re passionate about?

Arka Serezh: I moved to the United Kingdom when I was eighteen to study mechanical engineering, and I got really interested in 3D printing, partly because being able to 3D model something and then print it and get it into the real world—sometimes in just a day—is fascinating. I kept refining my skill at 3D modeling because I wanted to make more interesting things. I realized that I’m really interested in aesthetics—I wanted to design beautiful things. So, I’ve printed hundreds of objects over the past nine years, mostly for fun. I have a 3D printer in my dining room.

At the same time, I was trying to figure out professionally what I wanted to do. I always preferred taking my own initiative and didn’t like being told what to do. After a couple of terrible internships, I realized that I’m much better off learning things by myself than being put into someone else’s box. So, in 2020, I dropped out from my master’s degree to start a company that applied machine learning to find optimal solutions for engineering drones and cars. For example, if you want a drone to fly longer, you need a bigger battery, which means more weight, which means you need different motors, different electronics, a different chassis. It’s complex to find those trade-offs, so we developed a platform where engineers can plug in their parameters and then run optimization with AI to figure out the best solution. It was my first shot at entrepreneurship, and it was heavily on the engineering side—it wasn’t really aesthetic. At that point, I didn’t quite realize that I was missing that.

We managed to raise $1.7 million, but we realized that it’s impossible to sell this type of solution for a range of reasons. So, we wound down the company, and I got lost again because I knew I didn’t want to work within that industry, but I didn’t know what I wanted to do next. I worked at a range of early-stage medical technology hardware companies. That’s when I realized that I’m much more keen on design and aesthetics rather than pure engineering and figuring out the optimal solution for a problem.

Out of curiosity, I started learning more about architecture. I got a job with a construction robotics startup in the United States, and I helped them figure out how to take a robotics business to market in the construction industry. I knew that robotics could completely transform construction, but that’s a field you need to understand before trying to introduce robotics into it. You need to be on-site, you need to understand the workflows, you need to understand how the industry works.

I started wondering what kind of construction I wanted to work in. I looked at it from a materials perspective, starting with wood. I looked at the workflow of how you build framing and realized that it was very competitive. A lot of companies were going after this opportunity, and I wasn’t a big fan of wooden houses. Then I started looking at stone. By that time, I was familiar with early attempts of applying robotics to stone, and I found that very appealing from an aesthetics perspective. When you see a robot carving stone with water cooling the tool and the sun shining onto the stone, it just looks divine.

One of the obvious, go-to markets within that specific field is making sculptures and busts. If you look at the most beautiful buildings, such as Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, you will see that sculptures are integrated very deeply into the architecture. Since I was a kid, I really enjoyed stone buildings. When I was twelve, I visited Place Saint-Michel in Paris, which is just incredible. That strong memory pushed my curiosity further.

Here in the UK, we have many stone buildings, which means there is a big restoration market. So, I started diving deeper into and learning more about this industry by speaking with architects and founders in construction. That led me to meet the CTO of AUAR, a company applying robotics to cutting timber. They had an available robot that was too small for their needs and taking up their space, which they were willing to let me take.

He introduced me to The Stonemasonry Company. They had all the infrastructure I needed to bring the robot to them and retrofit it to cut stone. So that’s what I did. I finished my first carving at 4 a.m. on December 24. I’m now working on improving the process and getting early clients.

The UK is where the stone renaissance is happening. The Stonemasonry Company innovated on post tensioning stone (a technique for creating whole flights of stairs that are only supported at the top and bottom without a wall to bear into, held in the air with steel cables tensioned within the stone, giving the impression that they are floating). They reapplied this technology and started developing whole buildings massively cheaper and faster than possible before. Yet, most of their work is done by hand, so it lacks ornamentation because of the time it would take to incorporate it.

Recently, robots have developed quite a lot. Now, they have the ability to bring back ornamentation. It’s still going to be cheaper to cut in straight lines, but now it can be much cheaper to do ornamentation than it used to be. We’re currently deeply integrating our robots into the manufacturing workflow of The Stonemasonry Company with a goal to automate as much as possible and run the factory 24/7.

Walker-Werth: Stonemasonry is typically associated with classical architecture, but what you’re doing is more innovative. Could you tell me a bit about the style that you like to do with stonemasonry and how that’s innovative and different aesthetically as well as technically?

Serezh: We’re hoping to pioneer a new style. Exactly what that style is right now is not totally clear. One of the fundamental questions in architecture is the question of the line. Do we want the line to be curved like in Art Nouveau? Do we want it to be straight like in Art Deco and more modernist buildings? Or do we want it to be a mix like in Gothic architecture? With robotics and the current state of things, it does make sense to choose at least a mixture of curved and straight lines. What it is going to enable in terms of style is yet to be seen.

I toured Antoni Gaudí’s work in Barcelona recently. He’s famous for Art Nouveau and very curved lines. My opinion is that when there are too many curves, it seems quite alien. I wouldn’t want to spend too much time in his buildings. Maybe it’s just too unfamiliar to me compared to, let’s say the Gothic style, which is much more prevalent throughout the world and much easier to see, so I’m more accustomed to it. But there is demand for a new aesthetics—something comfortable but innovative.

Can there be aesthetics where we, for example, see machined lines that are very well integrated into the design? There have been examples like this, particularly within 3D printing. The way 3D printing works is that it essentially heats up plastic and then puts down a layer down, then goes up and puts the next layer on top, gradually creating a 3D object. When you get close to a 3D-printed object, you will see the lines. Certain methods have gotten so good that you really cannot see the lines, but what is quite interesting is that if you add a texture, the lines can become an integrated part of the design. So, it looks really good, and the lines stop being a defining feature.

The question I’m asking myself right now is: Is there a certain aesthetics where we combine the finishing, manufacturing lines of the robot and integrate them in a way that looks good? Even in Sagrada Familia, if you look at the beams closely, you will see lines from how the stone was machined. But most people will never look, so the lines don’t matter much. When it comes to a sculpture, you cannot have those lines because people will admire it closely—you need to have a sculptor finish those lines by hand.

But with architecture such as the Ionic capital where the stone is three meters above you, you probably wouldn’t see those lines. That’s where you can get insane cost savings with robotic stone processing. But, as Ayn Rand demonstrated in The Fountainhead, it doesn’t make sense to use new methods to just copy-paste what previously was done. It’s a chance to innovate a better solution. What is the solution that integrates the benefits and the flows of this method with a new style of architecture? I don’t have an answer to that question yet, but I really hope to have it quite soon. Realistically, because my company is so new, it makes sense to focus on markets that already exist instead of pushing a new aesthetics and architecture on people. But I think that as we scale up, this is the question that we will be answering.

Walker-Werth: You mentioned Rand’s philosophy and how that’s inspired you. She talked about how ornamentation on buildings can sometimes be a dishonest attempt to make a building look like something it isn’t, such as sticking a Doric arch on the front of somebody’s ordinary house. But you used to see companies ornamenting their buildings in the Victorian era—if you look at railway stations in London, they’re covered in this beautiful ornamentation because the railways were trying to out-compete other competitors and present a certain image. Nowadays everything’s very bland and basic, I think largely because there’s not the money, and people lack creative spirit these days. Do you think ornamentation makes sense in modern architecture, and if so, when is it honest and integrated to use it?

Serezh: My company is pretty much based on the idea that we should bring back ornamentation. The question of honesty is something that I grapple with a lot with respect to this, particularly when it comes to experimentation and the final outcome on the building. We need to be able to experiment with new aesthetics because at the end of the day, you can’t fully grasp how a building will look in real life with a 3D model or virtual reality. If we want to push forward, we need to experiment, and some of those experiments are not going to be good.

I think that a lot of experiments in architecture right now have gone way too far. A lot of focus is on reusing wasted materials. I am a big fan of the circular economy—my dissertation was essentially on developing computer vision technology to improve it in factories—but there is a difference between strapping broken aluminum panels onto a building and calling it a marvel of architecture, or building a house out of it that looks completely horrific, versus being much more thoughtful about what is possible now and what we do can that looks good.

What looks good is a very difficult question. I’m a big fan of integration in architecture. For example, when you walk in Notting Hill, you really like that area because all the houses are built in a similar style, and it brings pleasure—there is ornament, there is a change of scenery that doesn’t make it look super boring. I believe ornamentation is really important within architecture. Architecture is a public art, and if you follow that logic, an architect is an artist, and we want to enjoy the art that comes out of it. Ornamentation can add beauty as part of a carefully designed building, an integrated street, or a larger development. It will look dishonest and fake when the ornamentation doesn’t integrate with the building’s purpose—Greek statues on a London townhouse, for example. But integration with a purpose—such as the statue of Atlas at the Rockefeller Center in New York or floral motifs on a building to match the planting on the street outside—can add the kind of beauty and detail that’s often missing today. You still see some basic use of sculpture in some modern buildings, but it either tends to be very basic or not well integrated with the building itself.

Modernist architects have produced some nice things, such as the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. But I believe the widespread blandness of modernist architecture is going out of fashion. People are bored with it. But I don’t think there is yet a holistic school of thought, the way Bauhaus was, to answer the question of what is the new aesthetics.

Bauhaus was such a small movement—I believe about six hundred students graduated from it, and only a little more than one hundred students got degrees. Yet somehow, alongside other things, it focused us on the simplest manufacturing methods, driving down costs, and making everything as minimalistic as possible. It doesn’t need to be a big movement to get change to happen.

Cutting costs, like Bauhaus encouraged, can make economic sense on a certain level, but as a result, we lose the cultural appreciation of ornamentation. When there is no ornamentation around us, people start designing other things such as interiors and even software without ornamentation as well. So gradually you start converging on this minimalism everywhere in the culture. I think we are at the stage where it’s gotten boring for people, and the question is: What’s next?

Walker-Werth: In what way do you see ornamentation helping both a designer and a potential client, such as a business or a homeowner, express an idea, and what themes would you be expressing through it?

Serezh: I was just in Barcelona for four days, and as I was walking around, there were certain things specifically related to ornamentation that brought me a lot of joy. For example, I was walking with my girlfriend past all these already beautiful buildings in Barcelona, and we saw the Royal Palace of Music and had to check it out because it looked incredibly beautiful. It had sculptures outside and a gorgeous interior. We went to see flamenco there, and it’s literally one of the most beautiful music halls I’ve ever been to—they have statues coming from the walls inside it, and the ceiling is made of stained glass windows. And it was all built in three years. I cannot really believe that all of that was built in three years in the early 20th century.

For me, architecture is about enjoying my life outdoors. I spent four months in Los Angeles last year, which is a city built for cars. It’s not built for humans. You cannot walk most places. It’s definitely one of the worst cities I’ve ever been to, and the architecture is quite horrific as well. It’s hard to build for humans in a city like that. For us in the UK, there is so much stone craft. It’s much easier to build a beautiful house here than in the United States because there is a certain expectation here, like in Barcelona. There, they started building everything in a traditional style, and then a couple of people came and said, “I want to stand out!” and hired Gaudí and built buildings like Casa Batlló, which is a quite weird but very beautiful building. It definitely stood out among all the other architecture. I was also in Madrid for two days before Barcelona, and the thing that I remember quite well from there is the street signs. They have a ceramic plate with a portrait of a person whom the street is named after or a certain activity which that street is known for. It’s quite simple to make, it looks fun, and I was impressed that they wanted to embody a certain celebration of the human spirit—something heroic, something glorifying. It gives you directions while at the same time expressing a positive idea.

That’s really what I want to do—create beautiful outdoor environments that celebrate human achievement.

Walker-Werth: How has Rand’s philosophy helped you in terms of how you’ve approached business and how you’ve approached thinking about your work and your values?

Serezh: I didn’t even know what integrity meant until I read The Fountainhead. She shows it through her characters in a way that you cannot unsee—through Howard Roark’s fierce commitment to building what he wants in his way and his refusal to compromise his ideas. If you read the introduction to the book, that’s exactly what she was trying to do—show the ideal man in the form of Roark and use other characters to portray his virtues and the opposite traits further.

Rand helped me realize that if I want to maintain integrity, I needed to pursue aesthetics. Growing up in a conservative family, I didn’t have much creative outplay. But once I read Rand’s books, studied integrity, and thought deeply about what’s important to me, what I wanted to work on, and what I want to create in the world, it became clear that aesthetics is a big part of it.

From there, I started figuring out what problem I wanted to solve in the market. Consumer electronics, websites, and so forth—all those things have really big problems. But with the way architecture is going, I saw an opportunity to apply the latest technology to take it in a better direction. I’ve never felt as satisfied working on anything, and I’ve never worked as hard on anything as what I’m doing right now, and I believe one of the core reasons for that is because I’m maintaining high integrity.

My goal is to build beautiful buildings, which is what Roark was doing. At the same time, I want to apply the latest industrial methods, which is a core element of Atlas Shrugged. In a way, I would not be doing what I’m doing right now if I wasn’t inspired by Rand. She also showed me the value of industrialization. As we grow up, we don’t really see what drives the world. Her stories show how different industries interconnect and support our technological society. I believe that working in manufacturing is one of the most important things that you can do because that’s what drives the world forward.

To commemorate Rand’s inspiration that inspired me to start Gondor Industries, I decided to make five marble busts of Rand for collectors and private individuals who were inspired by her novels. I came up with a concept where the pedestal for the bust is her books and commissioned a digital sculptor to design it. I named the robot after Steven Mallory, the hero and sculptor in The Fountainhead. In that sense, the robot is making the bust of its namesake’s creator. I hope it will be one of the greatest artistic tributes ever made to her work. The first bust is a study that we’re carving out of limestone and will be kept as property of the company. The five marble busts will be made per order, and only five will ever be made.

Walker-Werth: I can’t wait to see them!

This article appears in the Spring 2026 issue of The Objective Standard.

Trump’s immigration enforcement, however destructive, is ultimately the responsibility of voters. It’s their responsibility to reverse course

The post ICE Tyranny Is What Democracy Looks Like appeared first on New Ideal - Reason | Individualism | Capitalism.

Download video: https://www.youtube.com/embed/0gp_aaCzoX0