Below is a video of my spoken testimony and Q&A, along with my prepared remarks, for Thursday’s Senate Banking Committee hearing “Examining Insurance Markets and the Role of Mitigation Policies.”

January’s devastating LA fires were the biggest wakeup call yet that California has become significantly more endangered by out-of-control wildfires.

Fortunately, more and more Californians are starting to understand the root cause: a failure to practice climate resilience.

As a longtime resident of Southern California, I have long been frustrated that our leading politicians blame our fire problems on rising CO2 levels, a minor fire factor they have no real ability to affect—while ignoring the major factor they can directly affect: resilience.

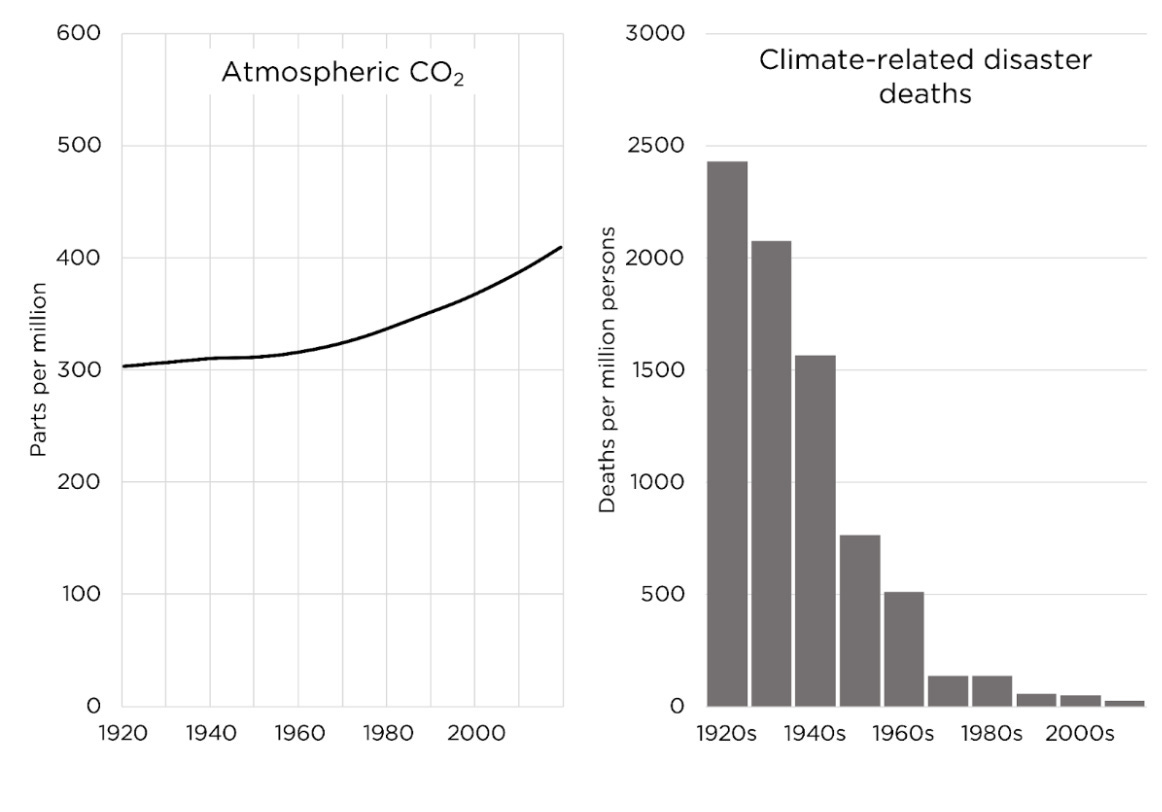

The last 100 years show that increasing resilience can more than offset any new dangers from rising CO2 levels. As evidence, the death rate from climate-related disasters has fallen 98%—and damages adjusted for GDP growth have not increased.1

Regardless of climate changes, we could radically reduce wildfire danger through 5 forms of resilience:

Crack down on human ignition

Reduce fuel load

Reduce proximity of homes to fuel

Increase fire-resistance

Build robust response capacities

We’ve failed at all 5.

California has failed to crack down on human ignition.

Many wildfires—and almost all in SoCal—begin with ignition from arson, accidents (especially from the homeless) and power line failures.2

The first two are easy to crack down on—yet we have failed spectacularly to do so.

California has failed to reduce fuel load.

Whether for dense forest or LA’s chaparral vegetation, reducing the amount of flammable material—through prescribed burns, brush clearing, fire breaks, or logging—dramatically limits fire’s potential.

Yet we let fuel load grow and grow.3

California has failed to reduce the proximity of homes to fuel.

Once a fire starts to spread, a huge factor in its destructiveness is proximity: how much human infrastructure is near flammable areas.

Yet we build more and more infrastructure in flammable areas.4

California has failed to increase fire-resistance.

Once a fire reaches urban areas, a major factor in its destructiveness is how fire-resistant the affected human infrastructure is.

Yet we have not increased fire-resistance to handle the danger caused by our other bad policies.

California has failed to build robust response capacities.

The last line of defense against a fire is effective firefighting that can respond quickly and at scale.

Yet before the recent fires, the LA fire department had a stagnant budget and insufficient water infrastructure.5

Why is California so bad at wildfire resilience? One major reason is “green” policies that prevent the major human impact needed to manage our naturally fire-prone forests and shrublands—such as reducing fuel load. “Green” fire management prohibitions are deadly.

An overlooked cause of California’s fire problems is a lack of free-market fire insurance. In a free market, fire insurance premiums would have risen dramatically in response to California’s failure to practice wildfire resilience—sending a crucial message.

But California shot the messenger.

Many Californians have experienced the situation my wife and I did when, in preparation for the birth of our first child, we bought our first home in Southern California. No private company would sell us fire insurance at any price; we could only get the government’s FAIR plan.

While climate catastrophists pretend that insurers’ withdrawal from California is due to overwhelming climate risk, this is absurd—not just because the major risk is lack of resilience, but because regardless of a risk’s cause, insurers can always profitably insure at some price.

There are many forms of insurance for things far riskier than fires in California—which, in high-risk areas, might be 1% of a home’s cost annually. Other forms of insurance often exceed 5%: athlete disability insurance, high-risk occupational insurance, even AppleCare!

As California’s failure to practice wildfire resilience was rising, we needed insurers to jack up premiums in proportion to the risk—especially for homes in fire-prone areas and/or homes with low fire-resistance. But our government prevented this, covering up its own failures.

California’s “Insurance Rate Reduction and Reform Act”—Proposition 103 from 1988—requires insurance companies to obtain prior approval from the state before increasing rates, and to base their rates only on past losses rather than future loss projections.6

Proposition 103 was voted into law in California specifically to prevent premium hikes in dangerous areas. As a result, predictably, insurance companies left markets where they could not turn a profit because the risk was too high compared to the premiums they could offer.

California also instituted a public FAIR “last-resort” plan, forcibly subsidized by private insurers, which provides insurance to homeowners regardless of risk, at artificially low prices. This directly incentivized home-building in highly fire-prone areas.7

Post-LA fires, California needs to embrace a free market in disaster insurance that will encourage us to increase resilience.

Instead, we have imposed even more restrictions on insurers, dictating which policies they can cancel and forcing them to fund government insurance.8

I will try to convince my government in California that the key to radically reducing wildfire danger—like all climate danger—is increasing resilience, including the free-market disaster insurance that incentivizes it.

But even if California won’t learn its lesson, I hope Congress does.

Congress should require the Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service to obtain NEPA categorical exclusions for proven wildfire-prevention tools—such as mechanical thinning and prescribed burns—so these lifesaving actions aren’t delayed by onerous, duplicative reviews.

Congress should direct the Fish and Wildlife Service to exclude wildfire prevention measures from review under the Endangered Species Act, given that wildfires themselves pose a far greater threat to wildlife than the measures to prevent them.

Congress should direct the Bureau of Land Management and the US Forest Service to incorporate additional mechanical thinning, prescribed fires, firebreaks, fuel breaks, and logging into their forest and resource management plans.

Congress should require the US Forest Service to abolish the “roadless forests” category within the national forest system—which unnecessarily restricts wildfire prevention efforts from accessing some of the most fire-prone areas due to lack of permanent roads.

Congress should direct the EPA to exempt prescribed burns from Clean Air Act air-quality calculations—or at minimum create a swift, automatic waiver—so land managers can use this proven wildfire-prevention tool without jeopardizing state Clean Air Act compliance.

Questions about this article? Ask AlexAI:

Popular links

EnergyTalkingPoints.com: Hundreds of concise, powerful, well-referenced talking points on energy, environmental, and climate issues.

My new book Fossil Future: Why Global Human Flourishing Requires More Oil, Coal, and Natural Gas—Not Less.

“Energy Talking Points by Alex Epstein” is my free Substack newsletter designed to give as many people as possible access to concise, powerful, well-referenced talking points on the latest energy, environmental, and climate issues from a pro-human, pro-energy perspective.

UC San Diego - The Keeling Curve

For every million people on earth, annual deaths from climate-related causes (extreme temperature, drought, flood, storms, wildfires) declined 98%--from an average of 247 per year during the 1920s to 2.5 per year during the 2010s.

Data on disaster deaths come from EM-DAT, CRED / UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium – www.emdat.be (D. Guha-Sapir).

Population estimates for the 1920s from the Maddison Database 2010, the Groningen Growth and Development Centre, Faculty of Economics and Business at University of Groningen. For years not shown, population is assumed to have grown at a steady rate.

Population estimates for the 2010s come from World Bank Data.